The Mummers Plays

This type of seasonal English folk drama was often performed at Christmas time from house to house. The play has been described as a strange processional dance and mimetic game with dialogue, however the term ‘mummers’ has a rather imprecise meaning. In parts of northern England, children with blackened faces have gone from house to house at Christmas time, sweeping the hearth, and they accompany their work with little humming noises, they are called mummers. There are also troupes of performers in England that have come out, and still come out every year to perform the action of the mumming plays, but they call themselves Guizers, Ploughjacks, Jolly Boys, Paper Boys, and many other names. The mummers play texts have come from many parts of England, but none of them can be given an earlier date than the eighteenth century. They are not the same as the courtly mummings of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, of which little has survived. Mumm is said to be derived from the Danish word Mumme, or Momme in Dutch, and signifies to disguise oneself with a mask; hence a mummer. In the second year of the reign of Henry IV (1399–1413), while he was having Christmas at Eltham, twelve aldermen of London and their sons rode in a mumming for the amusement of the king, for which ‘they had great thanks’ (Strutt’s Horde). Under the classical name of Ludi these masqueradings were frequently performed at court; and in the inventories of the time there are entries for suits of buckram and vizors, to represent men, women, birds, beasts, and angles. Jean Froissart (1337-1410?) tells us that after the coronation of Isabel of Bavaria, the queen of Charles VI of France, she had several rich donations brought to her by mummers in different disguisements; one resembling a bear, another an unicorn, others like a company of Moors, and others as Turks and Saracens (Chron. tom. i. iv. chap, 157, lord Berners translation). The mummeries of the lower classes usually took place at the Christmas holidays, and those that could not procure masks, rubbed their faces with soot or painted them; a practice alluded to by Sebastian Brant in his Ship of Fools (1494), which was translated by Alexander Barclay and printed by Richard Pynson in 1509. The blackened face was also a custom associated with the Morris dancers. It appears that many abuses were committed under the sanction of these disguisements, and for this reason an ordinance was established, by which a man was libel to punishment who appeared in the streets of London with ‘a painted visage’ (John Stow’s Survey of London, 1598 and 1603, fol. 680). In the third year of the reign of Henry VIII (1509-1547) it was decreed that no person should appear abroad like mummers, covering their faces with vizors, and in disguised apparel, under pain of imprisonment for three months. The same act enforced the penalty of twenty shillings against such as kept vizors in their houses for the purpose of mumming (Northbrooke’s Treatise, 1853, p. 105). Henry Bourne speaks of mumming practiced in the North about Christmas time, which consisted of ‘changing of clothes between the men and the women, who, when dressed in each other’s habits, go, from one neighbour’s house to another, and partake of their Christmas cheer, and make merry with them in disguise, by dancing and singing and such like merriments’. (Antiquitates Vulgares, 1725, chap. xvi)

In the hundreds of texts and fragments of the Mumming plays collected, there are two elements in common; they are all seasonal and they all contain a death and resurrection. The typical form of the mummers play has a presenter, usually Father Christmas, Headman or Fool, but occasionally a Devil or an old woman – calls out a Champion, having first cleared a space for the action. This Champion’s name is frequently St George or Prince George. He is followed by an antagonist-sometimes the Turkish Knight, sometimes the King of Morocco, and sometimes Slasher. They fight and the Champion kills his boastful antagonist. A doctor is called for and he effects the corpse’s resurrection. Characters equipped with musical instruments and collection-boxes then appear to collect money from the spectators while a dance is performed. The central combat can be extended and supplemented by subsidiary characters; and the dispute that leads to the combat can be related to rival claims to a woman, frequently the King of Egypt’s Daughter. All of the performers were strictly male, although some dressed as women and some wore elaborate head-gear and costumes.

Three types of ceremony are related by Alan Brody: The Hero-Combat, the most familiar type of ceremony in which a protagonist meets and antagonist in direct combat. One of the two falls and is subsequently revived by a third party who acts as a doctor. There are never less than three performers although there can be many more as well as many combats, deaths and resurrections. It is only the combat, death and revival that give this particular type of ceremony its shape. The next type is the Sword Dance Ceremony, and there are two obvious points that separate it from the Hero-Combat. First there is a linked sword dance, never performed by fewer than five men. The second is the manner of death, which does not result from direct hand-to-hand combat but from the action of the community of dancers on a single character. In most cases this is achieved by placing a ‘lock’ of swords around the neck of the victim and each of the dancers suddenly and simultaneously withdrawing his own sword. In some cases, this ceremony apparently included such figures as the fool or the Beelzebub (perhaps, the same person under different names) the ‘Bessy’ and the Hobby-horse. The third type, the Wooing ceremony, is confined to the East Midland counties of Rutland, Lincolnshire, Leicestershire, and Nottinghamshire. This play also has its combat between two opponents and a death and resurrection; however this does not appear to be the central significant action. Although it does occur in one form or another in every example, the combat can happen anywhere and at any time during the performance, and it can be between any two players. It is the wooing action itself that emerges as the signigicant constant element from the eighty-five examples of this type. There is always a ‘female’ who is wooed and won by a clown. A second older ‘female’ often carrying a bastard child whose fatherhood she tries to assign to the clown, is also common. It is the introduction of the sexual theme in the wooing of the lady that gives this type its distinctive feature. There are two other features worth nothing; the Wooing Ceremonies are confined to the East Midland counties and the New Year season. The Hero-Combat, on the other hand, exists everywhere, including the East Midlands, and is found as the Pace Egg Play at Easter, and the Soul-Cakers Play at All Souls.

The all male cast of the Minehead Mummers.

The Pace Egg Play performed at Easter by the schoolchildren of Midgley.

Grenoside Sword Dancers form a lock with their swords over the head of their captain. When the fur hat is knocked off, he falls.

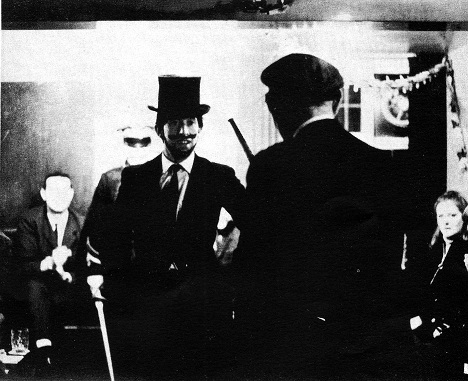

The Bampton Mumming Play is performed in the village pubs. Note the ‘doctor’ with top hat, mustache, and beard.

The Marshfield Paper Boys with ‘King William’ and ‘Little John’ locked in combat.

This page contains information found in The Medieval Theatre, Glynne Wickham, (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1974); The English Mummers and their Plays: Traces of Ancient Mystery, Alan Brody, (London, 1970); The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England, Joseph Strutt and William Hone (London 1838); The Pictorial History of England, George L. Craik and Charles Mac Farlane (London, 1839); The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21), Volume V, Development of the Mummers Play.