Robin in Music and Literature

From the sixteenth century onwards, ‘Robin’ appears in song. Whether it be Gentle Robin, Jolly Robin,(1) Bonny Sweet Robin, or Robin Hood, the reference can be to the famous outlaw, or a favourite bird or flower, or someone else. There may be some influence from the May Games,(2) perhaps a faint echo of the earlier Robin and Marion made famous in music and text by Adam de la Halle. The music for Bonny Sweet Robin occurs in several sources between 1597 and 1621, and the tune was used for a variety of other lyrics between 1594 and 1690. There also survives several Scottish variants of text and tune, printed in the eighteenth century. The majority of the musical sources are scored for lute, although some are for cittern, some for bandora, some for viol, and others for a consort of instruments.

Jolly Robin can be found in literature as early as the fourteenth century, and Robin Hood himself is given this name in the ballad Robin Hood and the Butcher and The Jolly Pinder of Wakefield. A ‘Brown Robin‘ appears in two versions of the ballad with that name, and also in Brown Robyn’s Confession, and in Hind Henry and May a Row, and one version of Rose the Red and White Lily. The theme of the greenwood is evident, and Brown Robin is the lover or husband of May Margerie, or May a Row, in Hind Henry and May a Row, and again of White Lily in Rose the Red and White Lily. Robin Hood is sometimes confused with the mythological figure Robin Goodfellow.

1. Jolly Robin appears to be the common name for a country fellow.

2. Robin Hood and Marian appear in the Fourth Booke of Ayres, by Robert Jones. ( see No. 9 below)

(1) A Lutel Soth Sermun, c. 1250, Author unknown

‘A Lutel Soth Sermun’ occurs in manuscripts British Library, MS Cotton Caligula A.ix and Oxford, Jesus College, MS 29. (The Cambridge History of Medieval English literature, p. 81, David Wallace, Cambridge University Press, 1999). The text of this mid-thirteenth century sermon is about 100 lines in length. In the Miller’s Tale (line 3555) by Geoffrey Chaucer is found the following: ‘But Robin may not wite of this, thy knave / Ne eek thy mayde (maiden) Gille, I may not save’. Robin is the servant of the Miller. The short poem Robene and Makyne by the 15th-century Scottish makar Robert Henryson (1430?-1506?) is an early example of Scottish pastourelle; Robene is the shepherd who refuses the country maid Makyne’s love. It is written in a form of ballad stanza, in which the speech and humour of the Scottish peasantry assimilates the traditional French genre.

(2) Dixieme Pastourelle, c.1260, attributed to Gilbert de Berneville

Lines 28, 42, 56

Et Robins el bois: Dorenlot And Robins in the wood: tra la la?

The trouvère Gilbert de Berneville, about whom little is known, was thought to be born born at Courtray in Belgium, although there is some suggestion he was born in the village of Berneville, near Arras in northern France, the birthplace of Adam de la Halle. The Huitieme Pastourelle (c.1260) has the characters Robin, Guis (Guy), Marion and Rogier (Roger). These and other pastourelles (and motets) that mention Robin and/or Marion are found in Encyclopedie Theologique edited by J.P. Migne. The thirteenth century romance Jehan et Blonde by Philippe de Remi (d. 1265) may have originally been composed in the 1240s. It is the story of Jehan (John), an ambitious and honest young man who goes to England to seek his fortune. He wins the job of squire to the Earl of Oxford, and falls in love with the young beauty Blonde, the earl’s daughter who is of higher station. John is later made Count of Dammartin in France, and his varlet (servant) is the ever-faithful Robin. The action moves back and forth between Northern France and Southern England. (see Jehan et Blonde, poems and songs, Barbara Nelson Sargent-Baur, 2001)

(3) Le Jeu de Robin et de Marion, c. 1283, by Adam de la Halle (1237?-1288?)

Opening song:

Closing song:

Medieval French Plays, Richard Axton and John Stevens, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1971, pp. 263 and 301.

.

(4) Mirour de l’ Omme, c. 1376, by John Gower (1330?-1408)

Mirour de l’ Omme, (The Mirror of Mankind), William Burton Wilson, East Lansing Colleagues Press, 1992, pp. 119 and 279. Gower appears to have written this work in the years 1376-79, it is likely he was referring to the ‘Robin’ of Adam de la Halle; was Chaucer of the same mind, or was he referring to Robin Hood? (see below) It is not know if Gower knew Langland, the author of Piers Plowman, both were writing on the same general subjects in London at about the same time.

.

(5) Troilus and Criseyde, c. 1385, by Geoffrey Chaucer (1343?-1400)

The Book of Troilus and Criseyde, ed. Robert Kilburn Root, 1926, Book Five, p. 372, 1170-1176. Jolly Robin appears in this phrase spoken by Pandarus to himself when Troilus is convinced that he can see Criseyde returning. Chaucer’s inspiration for this tale is from Giovanni Boccaccio’s poem II Filostrato (c. 1338), he substitutes an English phrase for the original Italian, (VII. 10.) which in translation reads: ‘this poor wretch expects a wind from Mongibello.’ Chaucer’s meaning is unclear, possibly the phrase means ‘from the land of fantasy’ in any case, the proverb he uses in Troilus (Book two, 861) ‘Thei speken, but thei benten nevere his bowe’ is used in later reference to Robin Hood; and in the meeting in The Friar’s Prologue and Tale, (section two) ‘under this grene shawe’ with the yeoman in green, from ‘the north contree,’ with bow and arrows, we can see a similar formula to the ballads of the outlaw hero. His friend John Gower had already mentioned ‘Robin.’ (see above) A later version of Chaucer’s tale can be found in Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida (c. 1601–02). The original of the tale appears to be the 12th century Le Roman De Troie by Benoit de Sainte-Maure.

.

(6) King Edward and the Shepherd, late 14th century, Author unknown

Middle English Metrical Romances, ed. Walter Hoyt French and Charles Brockway Hale, 1964, p. 954, 121-128. In this poem, Edward III meets Adam, a shepherd, by a river-side one morning in May. They engage in conversation and the shepherd, unaware of the others identity, complains of the king’s men, who take his beasts, and at best pay with a tally. Edward is concerned about his good name, so he pretends to be a merchant who has a son with the queen who can get any boon of her, so the shepherd shall have what is due to him. That is four pound two shillings, says Adam, and the ‘merchant’ shall have seven shillings for his service. It is arranged that the shepherd shall come to court the next day. Where will I find you and how are you called says the shepherd, my name is Joly Robyn says Edward, men know it well and fine in both bowers and hall, the porter will give you entry so you may speak with me………….. (For a complete version of this poem, see Other Tales)

.

(7) A Robyn, c. 1520, by William Cornysh (1465?-1523)

A transcription from the Song-Book of Henry VIII. Brit. Mus., Add. 39122, in The Poems of Sir Thomas Wiat, ed. A. K. Foxwell, 1913, pp. 62-63.

.

(8) A Robyn, c. 1535, by Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542)

|

|

|

From Egerton MS. 2711 (Brit. Mus.) in Collected poems of Sir Thomas Wyatt, ed., K. Muir and P. Thomson, 1969, pp. 41-42. This poem has a different text to the song by Cornysh, (see above) which must be an earlier source.

.

(9) Twelfth Night, Act iv. scene 2, c. 1600, by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

| Clown. | Hey Robin, jolly Robin (singing) |

| Tell me how thy lady does | |

| Malvolio. | Fool——- |

| Clown. | My lady is unkind, perdy |

| Malvolio. | Fool——- |

| Clown. | Alas, why is she so |

| Malvolio. | Fool, I say—— |

| Clown. | She loves another.—-Who calls, ha? |

Shakespeare appears to have borrowed from the poem by Wyatt. (see above)

.

(10) Hamlet, Act iv. scene 5, c. 1601, by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

| Ophelia. | There’s fennel for you, and columbines: there’s rue for you; and here’s some for me: we may call it herb-grace o’ Sundays: O you must wear your rue with a difference. There’s a daisy: I would give you some violets, but they withered all when my father died: they say he made a good end,– |

| (sings) For bonny sweet Robin is all my joy. | |

| Laertes. | Thought and affliction, passion, hell itself, She turns to favour and to prettiness. |

| Ophelia. | (sings) And will he not come again? And will he not come again? No, no, he is dead: Go to thy death-bed: He never will come again. His beard was as white as snow, All flaxen was his poll: He is gone, he is gone, And we cast away moan: God ha’ mercy on his soul! And of all Christian souls, I pray God. God be wi’ ye. |

It has been suggested that Ophelia’s ‘bonny sweet Robin’ is the bird in the branches of the willow tree, or the ‘wake- robin’ or ‘long purple’ flower, which was both know to Shakespeare and relevant to Ophelia’s situation.

.

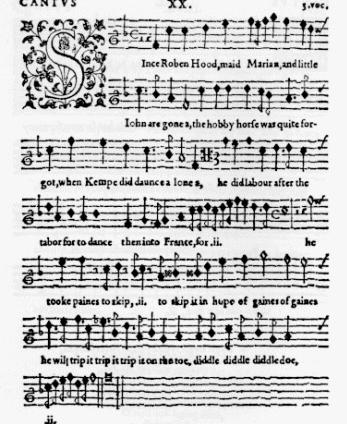

(11) Since Robin Hood, 1608, by Thomas Weelkes (1576?-1623)

.

Thomas Weelkes was an English composer and organist. He published his first book of madrigals in 1597 and was appointed organist at Winchester College the following year. His next two books of madrigals, his greatest, were soon published (1598, 1600), and a final volume was published in 1608. Weelkes is noted for his word painting, lively rhythms, and highly developed sense of form and structure. The term ‘madrigal’ has two distinct, meanings. Originally it was a poetic and musical form of fourteenth century Italy, a short lyric poem, usually of love or pastoral life, often set to music as a song for several voices, without instrumental accompaniment. The madrigal originated in part from the frottola, in part from the resurgence in interest in vernacular Italian poetry, and also from the influence of the French chanson and polyphonic style of the motet, as written by the Franco-Flemish composers who had naturalized in Italy during the period. The later form of the madrigal was the sixteenth or seventeenth century secular vocal music composition, which was revived and adopted by composers throughout Europe. The earliest examples of this genre date from Italy in the 1520s. The English madrigal flourished from the 1580s to the 1620s. (see Oxford Grove Music Encyclopedia; Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms; Columbia Encyclopedia)

.

(12) A Musicall Dreame or Fourth Booke of Ayres, 1609, by Robert Jones (1570?-1615?)

The English School of Lutenist Song Writers (Second Series) ed. E. H. Fellowes, 1927, pp. 55-57. This work, and the one above, are contemporary with Shakespeare’s plays.

.

(13) Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, 1765, by Thomas Percy (1729-1811)

|

|

Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, revised ed., Henry B. Wheatley, 1876, Vol II, pp. 185-187. Percy calls his edition of ‘A Robyn, Jolly Robyn’ the ‘proper readings of the old song itself’. He gives his source as Dr. Harrington’s poetical MSS. which has been marked No. I (Scil. p. 68.) This is in fact, A Robyn attributed to Thomas Wyatt in Egerton MS. 2711. (see above) Percy tells us that the manuscript contains many of the Poems of Sir Thomas Wyat, with most of the contents attributed to him by marginal directions in an old but later hand; this led Percy to suggest that some of the poems (including A Robyn) may have been composed by someone else. In the edition of Wyatt’s poems by Muir and Thomson, (1969) we are told that the Egerton MS, contains copies of his poems ‘written in a clear and elegant hand,’ a few with corrections by the poet himself; also twelve poems in his own writing, and the works of others, including Sir John Harrington. Furthermore, the MS. was used by one of the Harrington family in the seventeenth century for jottings on a variety of topics, making the poems difficult to decipher.

.

(14) ‘Bonny sweet Robin’ refrain (Dublin, Trinity College, MS D.1.21, p. 113)

.

(15) ‘Hey jolly Robin’ (Dublin, Trinity College, MS D.1.21, p. 113)

.

Music Sources

Printed Sources

| Anthony Holborne, Cittharn Schoole, London, 1597 |

| Title: Bonny sweet Robin |

| Thomas Ravenscroft, Pammelia, London, 1609 |

| Title: A Round of three Country Dances in One text |

| of tenor: Robin Hood, Robin Hood, said little John |

| Thomas Robinson, Schoole of Musicke, London, 1603 |

| Title: Robin is to the greenwood gone |

| Thomas Robinson, Schoole of Musicke, London, 1603 |

| Title: Bonny sweet boy |

Manuscript Sources

| Cambridge University Library | Dd.2.I I. | f. 53.r. | |

| Title: Robin | Anon. | ||

| Cambridge University Library | Dd.2.I I. | f. 66.r. | |

| Title: Robin | Composed by Dowland | ||

| Cambridge University Library | Dd.2.I I. | f. 66.r. | |

| Title: Bonny sweet boy | Anon. | ||

| Cambridge University Library | Dd.3.18 | f. I I.r. | |

| Title: Robin is to the greenwood gone | Anon. | ||

| Cambridge University Library | Dd.9.33. | f. 29.v, 30. | |

| Title: Robin | Composed by Dowland | ||

| Cambridge University Library | Dd.9.33. | f.8I.v. | |

| Title: Robin Hood | Anon. | ||

| Cambridge University Library | Dd.9.33. | f. 82.r. | |

| Title: Bonny sweet boy | Anon. | ||

| Cambridge University Library | Nn.6.36. | f. 19.v, 20. | |

| Title: Robin | Anon. | ||

| Cambridge Fitzwilliam Museum | ‘Fitzwilliam Book’ | Fitzwilliam No. 15. | |

| Title: Robin | reprinted: composed by J. Munday | ||

| Cambridge Fitzwilliam Museum | ‘Fitzwilliam Book’ | Fitzwilliam No. 128. | |

| Title: Bonny sweet Robin | reprinted: composed by G. Farnaby | ||

| Dublin, Trinity College | ‘Ballet Book’ | D.I.21. | p. 27. |

| Title: Bonny sweet Robin | Anon. | ||

| Dublin, Trinity College | ‘Ballet Book’ | D.I.21. | p. 104. |

| Title: none | Anon. | ||

| Dublin, Trinity College | ‘Ballet Book’ | D.I.21. | p. 113. |

| Title: Robin Hood is to the greenwood gone | Anon. | ||

| Glasgow University Library | ‘Euing Book’ | R.d.43. | f.46.v,47. |

| Title: Robin Hood | composed by Ascue | ||

| London, British Museum | ‘Pickering Book’ | Eg.2O46. | f. 22.v. |

| Title: Sweet Robin | Anon. | ||

| London, British Museum | ‘Pickering Book’ | Eg.2O46. | f. 35.r. |

| Title: Sweet Robin | Anon. | ||

| London, British Museum | Add. 17786. | p. 15.r. | |

| Title: My Robin is to the, etc. | Anon. | ||

| London, British Museum | Add. 23623. | f. 13.v. | |

| Title: Bonn well Robin | composed by J. Bull | ||

| London, British Museum | Add. 31392. | f. 25.r | |

| Title: Jolly Robin | Anon. | ||

| Washington, Folger Library | ‘Dowland Book’ | 1610.I | f. I6.v. |

| Title: Robin is to the greenwood gone | Anon. | ||

| Washington, Folger Library | V.a.159(olim 448.16) | f. 5.r. | |

| Title: Robin Hood | Anon. |

Other References

R. Johnson, Golden Garland of Princely Pleasures, 3rd edn., London, 1620 sig. D.8. v.: ‘Fair Angel of England, thy beauty so bright’, rubric: to the tune of Bonny sweet Robin [Pollard STC, 14674; reprinted 1690: Wing STC,J 8o4A].

R. Johnson, Crown Garland of Golden Roses [3rd edn.], London, 1659, sig. F.5.v. : ‘Fair Angel of England, thy beauty most bright’, rubric: to the tune of Bonny sweet Robin [Wing STC, J 791; reprinted 1662: Wing STC, J 792; the poem does not occur in the 1612 or 1631 edns. of the Crown Garland, Pollard STC, 14672, 14673].

Roxburghe Ballads, edd. J. W. Ebsworth and W. Chappell, 9 vols., London, 1871-99, I.181: ‘Fair Angel of England, thy beauty most bright’, rubric: to the tune of Bonny sweet Robin.

Roxburghe Ballads, VII.785, No. 9: ‘Now farewell, good Christmas’, rubric: tune of Bonny sweet Robin.

H. E. Rollins, Analytical Index to the Ballad-Entries … in the Stationers…, Chapel Hill (N.C.), 1924, p. 58 (No. 617), s.v. ‘April 26, 1594’: ‘Doleful adieu to the last Earl of Derby’, rubric: to the tune of Bonny sweet Robin.

H. Morris, ‘Ophelia’s “Bonny sweet Robin” ‘, Publications of the Modern Language Association, LXXIII (1958), 601-603.

E. S. Le Comte, ‘Ophelia’s “Bonny Sweet Robin” ‘, Publications of the Modern Language Assn., LXXV (1960), 480.