Robin Goodfellow

Robin Goodfellow is also known as Puck, or a Hobgoblin. In folklore, a Hobgoblin refers to tiny mischevious creatures that look like humans. They reside in human dwellings but are active only when humans are sleeping, doing menial work around the household and not expecting anything else other than food for their work. Hobgoblin, a familiar equivalent for a goblin, was at first apparently two words, Hob Goblin – Hob being a ‘Christian name’ for a mischievous spirit, and defined by the generic term or surname Goblin. The two-part name was extended to any goblin or imp and was then written as one word, Hobgoblin. Hob is a medieval nickname for Robert or Robin, and in some cases, Robin Hood is identified as a Hobgoblin or Robin Goodfellow. The first use of the word appears to be in 1530, where it is written as ‘Hobgoblyng- goblin’ (L’éclaircissement de la langue française. Par Jean Palsgrave, Paris, 1852, p. 231), but its origins go back before 1500 (The Devil and His Imps: An Etymological Inquisition, Charles P. G. Scott, Transactions of the American Philological Association (1869-1896), 1895, Vol. 26 (1895), pp. 99- 100).

1. The earliest reference to Robin Goodfellow is possibly found amongst a collection of short stories in a thirteenth century manuscript in the Bodleian Library (MS. Digby, No. 172, in The Foreign Quarterly Review, 1836-10: Volume 18, Issue 35. p. 189). Robinet, or Robin, seems to have the characteristics of a Hobgoblin (translation from the Latin):

‘Once Robinet was in a certain house in which certain soldiers were resting for the night, and, after having made a great clamour during the better part of the night, to their no small annoyance, he was suddenly quiet. Then said the soldiers to each other, ‘Let us now sleep, for Robinet himself is asleep.’ To which Robinet made reply, ‘1 am not asleep, but am resting me, in order to shout the louder after.’ And the soldiers said, ‘ It seems, then, that we shall have no sleep to-night.’ So sinners sometimes abstain for a while from their wicked ways, in order that they may sin the more vigorously after- wards …. The soldiers are the angels about Christ’s body, Robin is the devil or the sinner’.

2. The first mention of Robin Goodfellow by name is possibly found in the Paston Letter of 1489: ‘And thys is in the name of Mayster Hobbe Hyrste, Robyn Godfelaws brodyr he is, as I trow’ (James Gairdner, The Paston Letters, 1422-1509 A.D., A New Edition, Westminster, 1896, Vol. 3, p. 362).

3. Robin Goodfellow is often mentioned in Reginald Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft, first published in 1584. Scot sees Robin Hood as Robin Goodfellow: ‘There go as manie tales upon this Hudgin, in some parts of Germanie, as there did in England of Robin good fellowe. But this Hudgin was so called, bicause he alwaies ware a cap or a hood; and therefore I thinke it was Robin hood’ (The Discoverie of Witchcraft, Reginald Scot (being a reprint of the first edition published in 1584), London, 1886, p. 438).

4. In Anthony Munday’s comedy printed in 1584, the character Pedante says: ‘Ottomanus, Sophye, Turke, and the great Cham: Robin goodfellowe, Hobgoblin, the devill and his dam’ (Fidele and Fortunio, the Two Italian Gentlemen, London, 1909, Printed for the Malone Society by Charles Whittingham & co. at the Chiswick press. The Malone Society Reprints, p. n31).

5. In a rare anonymous collection of epigrams and satires, published in 1598, with the title, Skialetheia or, A Shadow of Truth in Certaine Epigrams and Satyres, there appears:

‘No; let’s esteeme Opinion as she is,

Fooles bawble, innouations Mistris’

The Proteus Robin-good-fellow of change’.

(Alexander B. Grosart, Skialetheia of Edward Guilpin, (1598), Manchester, 1878, Satyre VI, p. 62).

6. ‘Enter a Fairie at one doore, and Robin good-fellow at another.’ This is Shakespeare’s first mention of Robin Goodfellow in Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1600, 2 : 1 (Folio 1, 1623, p. 148).

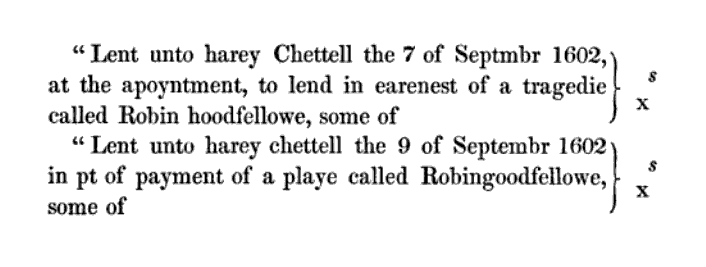

7. Henry Chettle was writing and perhaps wrote a play about Robin Goodfellow in September 1602, two years after Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, as can be seen in the two entries in Henslowe’s Diary:

In the first entry, which is confusedly worded, ‘tragedie’ has been struck out, and no other word substituted for it; but in the second entry ‘playe’ was interlined, ‘tragedie’ having been erased. Wether or not Henslow had in mind some confused notion of a connection between Robin Hood and Robin Goodfellow, is impossible to say (The Mad Pranks and Merry Jests of Robin Goodfellow: Reprinted from the Edition of 1628, with an introduction by J. Payne Collier, London, Reprinted for the Percy Society, 1841, pp. vii-viii).

8. Samuel Harsnet in 1603: ‘And if that the Bowle of curds & creame were not duly set out for Robin good-fellow the Frier, & Siffe the dairy-maide’ (A Declaration of Egregious Popish Impostures . . . . , London, 1603, p. 134).

9. A play about Robin Goodfellow was performed at Hampton Court in January 1604, followed by The Masque of Indian and China Knights (Anna of Denmark, Queen of England: A Cultural Biography, J Leeds Barroll, Philadelphia, 2001, p. 83).

10. Robin Goodfellow is a prominent character in Ben Jonson’s masque ‘Love Restored’ performed in 1612 and published in 1616.

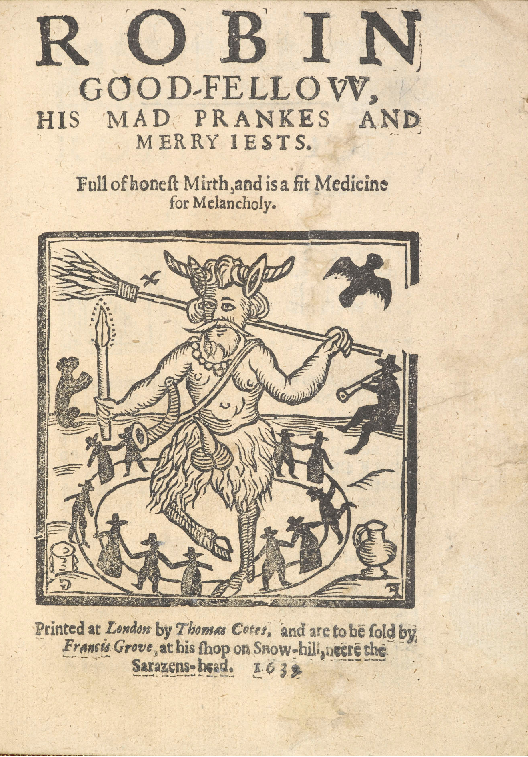

11. A jest book was published in 1628 with the title Robin Good-Fellow, His Mad Prankes and Merry Jests, and a second part in the same year, but it’s possible that something similar was first printed before 1588. Richard Tarlton, the celebrated comic actor died in September 1588, and Tarltons newes out of Purgatorye was entered in the Stationers Register on 26 June 1590. It was published with the title page ‘Tarltons Newes out of Purgatorie. Onelye such a jest as his Jigge, fit for Gentlemen to laugh at an houre, &c. Published by and old Companion of his, Robin Goodfellow’. The authorship of this work has been attributed, not certainly, to Thomas Nashe. It contains a passage which could refer to a sixteenth century version of Robin Good-Fellow, His Mad Prankes and Merry Jests – ‘Hob Thrust, Robin Goodfellow, and such like spirites, as they tearme them of the buttry, famozed in every olde wives chronicle for their mad merrye prankes . . . . (Tarlton’s Jests, and News out of Purgatory, James Orchard Halliwell, London, Printed for the Shakespeare Society, 1844, p. 55). There is a ballad entitled ‘Robin Good-Fellow’ in Bishop Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, first published in 1765, which is possibly founded upon Robin Good-Fellow, His Mad Prankes and Merry Jests, which is probably also the basis for an anonymous black-letter history in verse, printed early in the seventeenth century as a chap-book, with the title The Merry Pranks of Robin Good-Fellow: Very Pleasant and Witty – the small portions added, for the purpose of completing this deficient text, are inserted between brackets by J. Payne Collier.

The title page of the 1639 edition of Robin Good-Fellow, his Mad Prankes and Merry Jests. He is depicted with horns and a phallus and the shaggy legs and cloven hooves of a faun or goat. He is also carrying a broom and in the background are dancers in a ring and a piper (Courtesy of the British Library, Public Domain, Shelfmark, C.57.b.55).

12. Robin Goodfellow is a character in the play Grim the Collier of Croydon, attributed to William Haughton and John Tatham. The first known edition is dated to 1662. Grim the Collier of Croydon, John S. Farmer, The Tudor Facsimile Texts, 1912, p. 51, Act IV: ‘Enter Robin Good fellow in a suite of leather close to his body, his Face and Hands coloured russet-colour, with a Flayle.’

13. There is a two-page broadside ballad called ‘The Mad Merry Pranks of Robin Goodfellow’, printed around 1670. It has the lyrics for a song in the voice of Robin Goodfellow. It opens: ‘From Obrion (sic) in Fairy Land, / the King of Ghosts and Shaddows there, / Mad Robin, I at his Command, / am sent to view the Night-sports here’. The lyrics seem to have been influenced by Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with some echoes of the conversation between Robin and the Fairy in Act 2, Scene 1, and Robin’s speech while chasing the mechanicals in Act 3, Scene 1 just before he transforms Bottom. The ballad describes misleading wanderers, ‘Through Woods, through Lakes, / Through Bogs, through Brakes / O’re Bush and Bryer’, and shapeshifting: ‘Sometimes I meet them like Man, / sometimes an Ox, sometimes a Hound’. The same text is found in other broadsides (printed by other printers and with different woodcuts) from throughout the 17th century. The ballad is set to the tune of ‘Dulcina’, which was a popular tune of the day. The broadside has three woodcuts depicting Robin Goodfellow: the first shows him as a Green Man or man of the woods, hairy and covered with leaves; the second shows him in a faun-like guise in a woodcut recycled from an earlier jestbook on Robin Goodfellow; the third woodcut shows him in a mystical costume decorated with stars and moons (or perhaps even naked and covered with star and moon tattoos (Shelfmark: C.40.m.9. (51.). Public Domain, courtesy of the British Library).

14. Elisha Coles, An English Dictionary, Explaining Books . . . ., London, 1692: ‘Hobgoblins (q. Rob.) Robin-good-fellows’.

15. Thomas Keightley mention Robin Hood as an other name for Puck or Robin Goodfellow: ‘Puck . . . . his various appellations: these are Puck, Robin Good-fellow, Robin Hood, Hobgoblin’ (The Fairy Mythology, London, 1828, vol. 2, p. 118).

16. Robert Forby, The Vocabulary of East Anglia, London, 1830, Vol 2, p. 431: Proverbial Sayings . . . . “To laugh like Robin Good-fellow.” – i. e. A long, loud, hearty, horse-laugh. Thus the memory of the merry goblin still lives amongst us. But though his mirth be remembered, his drudgery is forgotten. His cream-bowl is never set; nor are any traces of the “lubber fiend” to be found on the kitchen hearth. He is even forgotten in the nursery.

17. ‘The Mad Pranks of Robin Goodfellow’ appears in Gammer Gurton’s Pleasant Stories of Patient Grissel, The Princess Rosetta, & Robin Goodfellow, and Ballads of The Beggar’s Daughter, The Babes in the Wood, and Fair Rosamond, Newly revised and amended, Printed for Joseph Cundall, Old Bond St., in the City of Westminster, 1845. There is another edition of 1846, by William John Thoms. This work contains part of Robin Good-Fellow, His Mad Prankes and Merry Jests (see no. 11 above).

18. Robin Goodfellow, a one-act comedy by Aurand Harris, premiered by the Harwich Junior Theatre in Massachusetts, 1974, and published by Anchorage Press, 1977. A children’s play based on the folk tales of Robin Goodfellow and scenes from the play Midsummer Night’s Dream.