William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare is affectionately known as ‘The Bard’ or ‘Sweet Swan of Avon,’ and although he has been described as the greatest writer in the English language, and the world’s pre-eminent dramatist, details about his life are sketchy. Shakespeare is a fairly common name in Warwickshire, and most of the information concerning the Bard is found in registrar records, court records, wills, marriage certificates and his tombstone in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon.

BIRTH AND PARENTAGE

The exact date of his birth is not known. Two 18th-century antiquaries, William Oldys and Joseph Greene, gave it as April 23, but in any case his birthday cannot have been later than April 23, since the inscription upon his monument is evidence that on April 23, 1616, he had already begun his fifty-third year. He was baptized in the Holy Trinity Church of Stratford-upon-Avon in Warwickshire (not far from the wilder and wooded district known as the Forest of Arden), on the 26th of April 1564. Of two adjoining houses forming a detached building on the north side of Henley Street, that to the east was purchased by John Shakespeare in 1556, but there is no evidence that he owned or occupied the house to the west before 1575. Yet this western house has been known since 1759 as Shakespeare’s birthplace, and a room on the first floor is claimed as that in which he was born (Halliwell-Phillipps, Letter to Elze, 1888).

Shakespeare’s father, John, was a Burgess of the recently constituted corporation of Stratford, and had already filled certain minor municipal offices. From 1561 to 1563 he had been one of the two chamberlains to whom the finance of the town was entrusted. In 1568 he attained the office of bailiff, and during his year of office the corporation for the first time entertained actors at Stratford. The queen’s company and the Earl of Worcester’s company each received from John Shakespeare an official welcome. On 5 Sept. 1571 he was chief alderman, a post which he retained till 3 Sept. of the following year. By occupation he was a Glover, but he also appears to have dealt from time to time in various kinds of agricultural produce, such as barley, timber and wool, and he was possibly a butcher as well. He is sometimes described in formal documents as a yeoman, and it is highly probable that he combined a certain amount of farming with the practice of his trade. He was living in Stratford as early as 1552, in which year he was fined for having a dunghill in Henley Street, but he does not appear to have been a native of the town, in whose records the name is not found before this time; and he may reasonably be identified with the John Shakespeare of Snitterfield, who administered the goods of his father, Richard Shakespeare, in 1561. At some date later than November 1556, and probably before the end of 1557, John Shakespeare married Mary Arden, youngest daughter of Robert Arden, a wealthy farmer of Wilmcote in the parish of Aston Cantlowe, near Stratford. William Shakespeare was not the first child. Joan was baptized in 1558 and a Margaret in 1562. The latter was buried in 1563 and the former must also have died young. A Gilbert was baptized in 1566, a second Joan in 1569, an Anne in 1571, a Richard in 1574 and an Edmund in 1580, who like his brother became an actor, in 1607.

EDUCATION AND EARLY YEARS

There are no records of Shakespeare’s education, but he probably went to King’s New School – a reputable free grammar school in Stratford, where he would have obtained a sound education, and learned Latin, Greek, theology and rhetoric – and may have had a Catholic upbringing. He had no title to rank as a classical scholar, and his lack of exact scholarship fully accounts for the ‘small Latin and less Greek’ with which he was credited by his friend, Ben Jonson. But John Aubrey’s report that ‘he understood Latin pretty well’ cannot be reasonably contested (Spencer Baynes, ‘What Shakespeare learnt at School’ in Shakespeare Studies, 1894, pp. 147 seq.). Shakespeare may also have seen plays by the travelling theatre groups touring Stratford in the 1560s and 70s.

In 1577 when he was about thirteen, Shakespeare may have left school, as his father’s fortunes had taken a turn for the worse. In any case, it is not likely that his school life was unduly prolonged. The chances are that he was apprenticed to some local trade. John Aubrey says that he killed calves for his father, and ‘would do it in a high style, and make a speech.’ Shakespeare’s father had to give a mortgage on his wife’s property of Asbies as security for a loan from her brother-in-law, Edmund Lambert. However, Lambert refused to surrender the mortgage on the plea of older debts, and an attempt to recover Asbies by litigation proved ineffectual. John Shakespeare’s difficulties increased. An action for debt was sustained against him in the local court, but no personal property could be found on which to distrain. He had long ceased to attend the meetings of the corporation, and as a consequence he was removed in 1586 from the list of aldermen.

MARRIAGE AND CHILDREN

At the end of 1582 when little more than eighteen and a half years old, Shakespeare was married, but his wife was already pregnant. Nicholas Rowe recorded the name of his wife as Hathaway, and Joseph Greene succeeded in tracing her to a family of that name dwelling in Shottery, one of the hamlets of Stratford. Her monument gives her first name as Anne, and her age as sixty-seven in 1623. She must, therefore, have been about eight years older than Shakespeare. Various small trains of evidence point to her identification with the daughter Agnes mentioned in the will of a Richard Hathaway of Shottery, who died in 1581, being then in possession of the farm-house now known as ‘Anne Hathaway’s Cottage.’ Shakespeare’s first child, Susanna, was baptized on the 26th of May 1583, and was followed on the 2nd of February 1585 by twins, Hamnet and Judith.

THE LOST YEARS

All the extant evidence points to the conclusion, that in the later months of the year (1585) Shakespeare left Stratford, and it was believed that he saw little of wife or children for several years. Recent archaeological evidence discovered on the site of his home shows that he was only ever an intermittent lodger in London. This suggests he divided his time between Stratford and London (a two or three-day commute). In his later years, he may have spent more time in Stratford-upon-Avon than scholars previously thought. The period between 1585 and 1592, were the ‘lost years’, and there is only one record of William’s name in the Stratford records in 1587, as owner of a contingent interest in property concerning Edmund Lambert. There is much speculation about these ‘lost years’, including stories that Shakespeare was exiled from Warwickshire for deer-stealing, that he became a scrivener, an apothecary, a dyer, a printer, a soldier, and that he worked at the London playhouses holding horses for theatre-goers.

THE LONDON THEATRE

By 1592, William was well-known enough as a writer and actor to be criticized by jealous rival Robert Greene (see no. above) in his pamphlet Groats-worth of Wit: ‘An upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers heart wrapt in a Players hide, supposes he is as well able to bumbast out a blanke verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes fac totum, is in his owne conceit the onely Shake-scene in a countrie.’ The play upon Shakespeare’s name and the parody of a line from Henry VI, one of his earliest history plays, which must have already been performed, makes this the first definite reference to him as an established London actor and playwright. Over the years, he became steadily more famous in the London theater world. Although it is difficult to determine the chronology of Shakespeare’s works, it is likely that by 1592 he had authored 11 plays, including Romeo and Juliet, Richard III and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. William Beeston (1606?-1682) asserted that Shakespeare ‘did act exceedingly well’ (John Aubrey) but few surviving documents directly refer to performances by him. His name is first on the list of the principal actors that performed in all of the plays in the First Folio.

Shakespeare’s plays began to be printed in 1594, probably with his tragedy Titus Andronicus. This appeared as a small, cheap pamphlet called a quarto because of the way it was printed. Eighteen of Shakespeare’s plays had appeared in quarto editions by the time of his death in 1616. Another three plays were printed in quarto before 1642. Shakespeare had multiple roles in the London theater as an actor and playwright, and he was a founding member and shareholder in a major acting company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, who performed before Queen Elizabeth on numerous occasions. Documentary evidence proves that he was a member of it in December 1594. The company would later become The King’s Men under the patronage of King James I (from 1603). From the summer of 1594 to March 1603 they appear to have played almost continuously in London, as the only provincial performances by them which are upon record were during the autumn of 1597, when the London theatres were for a short time closed owing to the interference of some of the players in politics. They travelled again during 1603 when the plague was in London, and during at any rate, portions of the summers or autumns of most years thereafter. In 1594 they were playing at Newington Butts, and probably also at the Rose on Bankside, and at the Cross Keys in the city. It is natural to suppose that in later years they used the Theatre in Shoreditch, since this was the property of James Burbage, the father of their principal actor, Richard Burbage. The Theatre was pulled down in 1598, and, after a short interval during which the company may have played at the Curtain, also in Shoreditch, Richard Burbage and his brother Cuthbert rehoused them in the Globe on Bankside. Julius Caesar was one of the first plays performed there. In 1608 the King’s Men took on a second theatre, a candlelit indoor venue at Blackfriars, whose expensive seats catered to a more elite audience. During his time in the company Shakespeare wrote many of his most famous tragedies, such as King Lear and Macbeth, as well as great romances, like The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest. Shakespeare prospered financially from his partnership in the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, and as well as writing more plays, he published poems and circulated his sonnet sequence in manuscript. His successes enabled him in 1597 to buy New Place, the second largest house in Stratford. However his success was tainted by tragedy, in 1596 his 11 year old son Hamnet, died.

FRIENDS

Some of his friends and fellow actors were Augustine Phillips, as well as John Heminge and Henry Condell, who afterwards edited his plays. Ben Jonson was also well know to Shakespeare, his company produced a number of Jonson’s plays, at least two of which (Every Man in His Humour and Sejanus His Fall) Shakespeare acted in. Jonson paid tribute in the prefatory verse that opens Shakespeare’s First Folio: ‘To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare and What He Hath Left Us’.

LATER YEARS AND DEATH

In 1612 Shakespeare was called as a witness in a court case. In March 1613 he purchased a ‘dwelling house or tenement’ built over one of the great gatehouses of the old Blackfriars priory, and a few months later, the Globe Theatre burned down. Among the last plays that he worked on was The Two Noble Kinsmen, which he wrote with a frequent collaborator, John Fletcher, most likely in 1613. The concluding years of Shakespeare’s life (1611–1616) were mainly spent at Stratford, but until 1614 he paid frequent visits to London. He made his will on the 25th of March 1616, and on 23 April, he died. Shakespeare was buried in Holy Trinity Church, where he had been baptised 52 years earlier. He was survived by his wife and two daughters.

SHAKESPEARE’S WORKS

It is thought that only one literary manuscript fragment in Shakespeare’s hand survives, ‘The Booke of Sir Thomas Moore’ (booke in this context meaning ‘play script’), which is now in the vaults of the British Library. Its main author seems to be the poet and playwright Anthony Munday (see no. below) but the text also appears to contain the handwriting of four fellow dramatists, one is possibly Shakespeare.

The earliest printed editions are our only source for what he actually wrote. The quarto editions are the texts closest to Shakespeare’s time. Some are thought to preserve either his working drafts (his foul papers) or his fair copies. Others are thought to record versions remembered by actors who performed the plays, providing information about staging practices in Shakespeare’s day. The Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, houses the world’s largest collection of Shakespeare’s printed works.

The first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays, the First Folio, was collated and published in 1623, seven years after the playwright’s death. Of the 36 plays in the First Folio, 18 had not yet been printed at all. It is this fact that makes the it so important; without it, many of Shakespeare’s plays, including Twelfth Night, Measure for Measure, Macbeth, Julius Caesar and The Tempest, might never have survived. The text was collated by two of Shakespeare’s fellow actors and friends, John Heminge and Henry Condell, who edited it and supervised the printing. They divided the plays into comedies, tragedies and histories, an editorial decision that has come to shape our idea of the Shakespearean canon. The Second Folio appeared in 1632, the Third in 1663-64, and the Fourth in 1685. Editors in every age—have addressed a variety of questions, including how to make sense of conflicting early versions of the plays. Shakespeare did not produce an authoritative print version of his plays during his lifetime, which accounts for part of his textual problem, often noted with his plays. This means that several of the plays have different textual versions. Other publishers have taken the text in new directions, from foreign-language editions to graphic novels.

The following list gives the date of the First Quarto of each play, and also that of any later Quarto which differs materially from the First (Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911, Vol. 24, Shakespeare, William by Edmund Kerchever Chambers, p. 776).

| The Quarto Editions. | |

| Titus Andronicus (1594). 2 Henry VI. (1594). 3 Henry VI. (1595). Richard II. (1597, 1608). Richard III. (1597). Romeo and Juliet (1597, 1599) Love’s Labour’s Lost (1598). 1 Henry IV. (1598}. 2 Henry IV. (1600). Henry V. (1600). |

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1600). The Merchant of Venice (1600). Much Ado About Nothing (1600). The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602). Hamlet (1603, 1604). King Lear (1608). Troilus and Cressida (1609). Othello (1622). |

Entries in the Register of copyrights kept by the Company of Stationers indicate that editions of As You Like It and Anthony and Cleopatra were contemplated but not published in 1600 and 1608 respectively. Quartos were purchased from Halliwell-Phillipps in 1858, and 107 copies of the 21 plays by Shakespeare printed in quarto before the 1642 theatre closures, due to the civil war, were finally digitized by the British Library in 2009.

The following table, which is an attempt to arrange the original dates of production of the plays without regard to possible revisions, may be taken as fairly representing the common results of recent scholarship. It is framed on the assumption that, as indeed John Ward tells us was the case, Shakespeare ordinarily wrote two plays a year; but it will be understood that neither the order in which the plays are given nor the distribution of them over the years lays claim to more than approximate accuracy (Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911, Vol. 24, Shakespeare, William by Edmund Kerchever Chambers, p. 777).

| Chronology of the Plays. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

THE POEMS

Only a small number of poems can definitely be attributed to Shakespeare. The narrative poem of Venus and Adonis was entered in the Stationers’ Register on April 18, 1593, and thirteen editions, dating from 1593 to 1636, are known. The Rape of Lucrece was entered in the Register on May 9, 1594, and the six extant editions range from 1594 to 1624. In 1599 the stationer William Jaggard published a volume of miscellaneous verse which he called The Passionate Pilgrim, and placed Shakespeare’s name on the title-page; only two of the pieces are certainly his. In 1601 Shakespeare contributed The Phoenix and the Turtle, an elegy on an unknown pair of wedded lovers, to a volume called Love’s Martyr, or Rosalin’s Complaint, which was collected and mainly written by Robert Chester.

THE SONNETS

The Sonnets were entered in the Register on May 20, 1609, by the stationer Thomas Thorpe, and published by him under the title Shakespeares Sonnets, never before Imprinted, in the same year. In addition to a hundred and fifty-four sonnets, the volume contains the poem, probably dating from the Venus and Adonis period, of A Lover’s Complaint. In 1640 the Sonnets, together with other poems from The Passionate Pilgrim and elsewhere, many of them not Shakespeare’s, were republished by John Benson in Poems Written by Wil. Shakespeare, Gent. Here the sonnets are arranged in an altogether different order from that of 1609 and are declared by the publisher to ‘appeare of the same purity, the Authour himselfe then living avouched.’ No Shakespearian controversy has received so much attention, especially during more recent years, as that which concerns itself with the date, character, and literary history of the Sonnets.

WHO INFLUENCED SHAKESPEARE

Shakespeare based many of his plays on the work of other contemporary playwrights, including Thomas Kyd, Christopher Marlowe, and Robert Greene, and there was influence from the plays of Seneca. He also recycled older stories and historical material. For example, Hamlet (c. 1601) is probably a reworking of an older, lost play (the so-called Ur-Hamlet), and King Lear is an adaptation of an older play, King Leir. For plays on historical subjects, Shakespeare relied heavily on two principal texts. Most of the Roman and Greek plays are based on Plutarch’s Parallel Lives (from the 1579 English translation by Sir Thomas North) and the English history plays are indebted to Raphael Holinshed’s 1587 Chronicles.

SHAKESPEARE’S INFLUENCE

Shakespeare’s impact on the theatre is immense, he created some of the most admired plays in Western literature, and also transformed English theatre by expanding expectations about what could be accomplished through characterization, plot, action, language and genre. His poetic artistry helped raise the status of popular theatre, allowing it to be admired by intellectuals as well as by those seeking pure entertainment. He also influenced a large number of writers in succeeding centuries, including Herman Melville, Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, and William Faulkner. Shakespearean quotations appear throughout Dickens writings and many of his titles are drawn from Shakespeare. One of Shakespeare’s greatest contributions is the introduction of vocabulary and phrases that enriched the English language, making it more colourful and expressive. Many original Shakespearean words and phrases have since become embedded in English, particularly through projects such as Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary which quoted Shakespeare more than any other writer.

See, Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Vol. 51, Shakespeare William by Sidney Lee, pp. 348-397; Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911, Vol. 24, Shakespeare, William by Edmund Kerchever Chambers, pp. 772-85; The British Library, ‘William Shakespeare’ (online); New World Encyclopedia, ‘William Shakespeare’ (online); Folger Shakespeare Library, ‘Shakespeare’s Life’, 1996-2020 (online); Royal Shakespeare Company, ‘Shakespeare’s Life and Times,’ 2020 (online); Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, ‘William Shakespeare Biography: Who was William Shakespeare?’ 2020 (online).

BIOGRAPHIES OF SHAKESPEARE

Thomas Fuller, in his ‘History of the Worthies of England (1662), attempted the first biographical notice of Shakespeare. John Aubrey, in his ‘Lives of Eminent Men’ (compiled before 1680; first printed in ‘Letters from the Bodleian,’ 1813, and re-edited for the Oxford Univ. Press by the Rev. Andrew Clark 1898), based his more substantial information on reports communicated to him by William Beeston (d. 1682), an aged actor, whom Dryden called ‘the chronicle of the stage.’ A few additional details were recorded in the seventeenth century by the Rev. John Ward (1629–1681), vicar of Stratford-on-Avon from 1662 to 1668, in a diary and memorandum-book written between 1661 and 1663 (ed. C. A. Severn, 1839); by the Rev. William Fulman, whose manuscripts are at Corpus Christi College, Oxford (with interpolations made before 1708 by the Rev. Richard Davies, vicar of Saperton, Gloucestershire); by John Dowdall, who travelled through Warwickshire in 1693 (London, 1838); and by William Hall, who visited Stratford in 1694 (London, 1884, from Bodleian MS.). Phillips in his Theatrum Poetarum (1675), and Langbaine in his English Dramatick Poets (1691), confined themselves to criticism.

In 1709, Nicholas Rowe became the first modern editor of Shakespeare’s plays, making the text more accessible through tools such as lists of characters and act and scene divisions. He prefixed a more ambitious memoir of Shakespeare than had yet been attempted to his edition of the plays, and embodied some new local Stratford and London traditions with which the actor Thomas Betterton supplied him. More information was collected by William Oldys, and was printed from his manuscript ‘adversaria’ as an appendix to Yeowell’s ‘Memoir of Oldys,’ 1862. Pope, Johnson, and Steevens, in biographical prefaces to their 18th century editions of Shakespeare, mainly repeated the narratives of their predecessors. In the Prolegomena to the Variorum edition of 1821 there was embodied a mass of fresh information derived by Edmund Malone (considered the best of the 18th century editors of Shakespeare) from systematic researches among official papers at Stratford, at Dulwich (the Alleyn MSS.), or in the Public Record Office, and the available knowledge of Elizabethan stage history, as well as of Shakespeare’s biography, was thus greatly extended. Francis Douce in his ‘Illustrations of Shakespeare’ (1807), and Joseph Hunter in ‘New Illustrations of Shakespeare’ (1845), occasionally supplemented Malone’s researches. John Payne Collier in his ‘History of English Dramatic Poetry’ (1831), in his ‘New Facts’ about Shakespeare (1835), his ‘New Particulars’ (1836), and his ‘Further Particulars’ (1839), and in his editions of Henslowe’s Diary and the Alleyn Papers for the Shakespeare Society, while throwing some light on obscure places, foisted on Shakespeare’s biography a series of ingeniously forged documents which have greatly perplexed succeeding biographers. Dyce specified the chief of Collier’s forgeries in the second issue of his edition of Shakespeare (G. F. Warner’s Cat. of Dulwich MSS.). James Orchard Halliwell (afterwards Halliwell-Phillipps) printed separately, between 1850 and 1884, in various privately issued publications, all the Stratford archives and extant legal documents bearing on Shakespeare’s career, many of them for the first time, and in 1887 he published massive materials for a full biography in his ‘Outlines of the Life of Shakespeare’ (4th edit.). Mr. F. G. Fleay, in his ‘Shakespeare Manual’ (1876), in his ‘Life of Shakespeare’ (1886), in his ‘History of the Stage’ (1890), and his ‘Biographical Chronicle of the English Drama’ (1891), adds some useful information respecting Shakespeare’s relations with his fellow-dramatists, mainly derived from a study of the original editions of the plays of Shakespeare and of his contemporaries; but many of his statements and conjectures are unauthenticated. Extensive information is supplied in Karl Elze’s ‘Life of Shakespeare’ (Halle, 1876; English translation, 1888), with which Elze’s Essays from the publications of the German Shakespeare Society (English translation, 1874) are worth studying. Prof. Dowden’s ‘Shakespeare Primer’ (1877) and his ‘Introduction to Shakespeare’ (1893), and Dr. Furnivall’s ‘Introduction to the Leopold Shakespeare’, are all useful. Sidney Lee in 1898 brought out ‘A Life of William Shakespeare,’ often reprinted in England and America, and translated into German 1901. Shakespeare’s Library (ed. J. P. Collier and W. C. Hazlitt), Shakespeare’s Plutarch (ed. Skeat), and Shakespeare’s Holinshed (ed. W. G. Boswell-Stone, 1896), trace the sources of Shakespeare’s plots. Alexander Schmidt’s Shakespeare-Lexicon, 1874 (ed. Sarrazin, 1902), and Abbott’s Shakespearean Grammar, 1869 (new edit. 1897), are valuable aids to a study of the text. Extensive bibliographies are given in ‘Lowndes’s Libr. Manual’ (ed. Bohn), and in Franz Thimm’s ‘Shakespeariana’ (1864 and 1871). A modern comprehensive edition appears in ‘The Life of William Shakespeare: A Critical Biography’, Lois Potter, Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

See, Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Vol. 51, Shakespeare William by Sidney Lee, p. 384; Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, ‘Publishing Shakespeare’ 1996-2020 (online).

EDITORS OF SHAKESPEARE

| 1709 Nicholas Rowe, The Works of Mr. William Shakespear in Six Volumes; Adorn’d with Cuts |

| 1725 Alexander Pope, The Works of Shakespear in Six Volumes, Collated and Corrected by the former Editions |

| 1726 Lewis Theobald, Shakespeare Restored; or, A Specimen of the Many Errors As Well Committed As Unamended by Mr. Pope, in His Late Edition of This Poet |

| 1728 Alexander Pope, The Works of Mr. William Shakespear: In Ten Volumes |

| 1733 Lewis Theobald, The Works of Shakespeare in Seven Volumes |

| 1740 Lewis Theobald, The Works of Shakespeare: In Eight Volumes, Collated with the Oldest Copies, and Corrected |

| 1744 Thomas Hanmer, The Works of Shakespear: In Six Volumes. Carefully Revised and Corrected by the Former Editions, and Adorned with Sculptures Designed and Executed by the Best Hands |

| 1745 Thomas Hanmer, The Works of Shakespear: in Six Volumes |

1747 Alexander Pope and William Warburton, The Works of Shakespear in Eight Volumes: The genuine text (collated with all the former editions, and then corrected and emended) is here settled being restored from the blunders of the first editors, and the interpolations of the two last : with a comment and notes, critical and explanatory |

1752 Lewis Theobald, The Works of Shakespeare: In Eight Volumes: Collated with the Oldest Copies, and Corrected : With Notes Explanatory and Critical |

| 1765 Samuel Johnson, The Plays of William Shakespeare : In Eight Volumes, With the Corrections and Illustrations of Various Commentators |

| 1766 George Steevens, Twenty of the Plays of Shakespeare: Being the Whole Number Printed in Quarto during His Life-Time, or before the Restoration (four volumes) |

| 1766 Alexander Pope The Works of Shakespear: In Eight Volumes |

| 1767-68 Edward Capell, Mr. William Shakespeare: His Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies: set out by himself in quarto, or by the players, his fellows in folio, and now faithfully republish’d from those editions in ten volumes octavo, with an introduction |

| 1771 Thomas Hanmer The Works of Shakespear: In Six Volume, Adorned with Sculptures |

| 1773 Samuel Johnson and George Steevens, The plays of William Shakespeare in ten volumes : with the corrections and illustrations of various commentators |

1774 Bell’s edition of Shakespeare’s plays, : as they are now performed at the Theatres Royal in London; : regulated from the prompt books of each house by permission; with notes critical and illustrative; by the authors of the Dramatic censor |

| 1780 Edmond Malone, Supplement to the Edition of Shakspeare’s Plays Published in 1778 by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens.: In Two Volumes: Containing Additional Observations by Several Of the Former Commentators: To Which Are Subjoined the Genuine Poems of the Same Author, and Seven Plays That Have Been Ascribed to Him; with Notes by the Editor and Others |

| 1784 Stockdale’s Edition of Shakespeare: Including, in One Volume, the Whole of his Dramatic Works with Explanatory Notes Compiled from Various Commentators |

| 1785 Isaac Reed, Samuel Johnson, George Steevens, The Plays of William Shakspeare: In Ten Volumes: with the corrections and illustrations of various commentators |

| 1786-94? Joseph Rann, The Dramatic Works of Shakspeare: In Six Volumes: with notes |

| 1788 Bell’s Edition of Shakspere (twenty volumes) |

| 1790 Samuel Ayscough, Shakspeare’s Dramatic Works: with Explanatory Notes (three volumes) |

| 1790 Edmond Malone, The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare: In Ten Volumes: Collated Verbatim with the Most Authentick Copies, and Revised, with the Corrections and Illustrations of Various Commentator: to which are added, an essay on the chronological order of his plays; an essay relative to Shakspeare and Jonson [sic]; a dissertation on the three parts of King Henry VI; an historical account of the English stage; and notes |

| 1792 The Dramatick Works of William Shakespear: Printed Complete from the Best Editions of Samuel Johnson, George Stevens and E. Malone ; to Which Is Prefixed the Life of the Author (eight volumes) |

1793 The plays of William Shakspeare: In fifteen volumes. With the corrections and illustrations of various commentators. To which are added, notes by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens. The fourth edition. Revised and augmented (with a glossarial index) by the editor of Dodsley’s collection of old plays |

| 1797 The works of William Shakspeare, containing his plays and poems: To which is added a glossary. In seven volumes |

| 1803 Isaac Reed produced a revised version of George Steevens works of Shakespeare, with additional notes left by Steevens, which is generally known as the ‘first variorum’ edition (twenty one volumes), meaning an edition containing notes by various scholars or critics |

| 1809 Alexander Chalmers issued a nine volume edition of Shakespeare, with an abridgement of the notes of Steevens and a life of Shakespeare (probably by Chalmers), with a new edition in 1823 |

| 1813 The ‘first variorum’ reprinted with very little changes, known as the ‘second variorum’ (twenty one volumes) |

| 1821 The ‘third variorum’ begun by Edmund Malone and completed by James Boswell the younger, which also incorporates Steevens’s notes (twenty one volumes) |

| 1863-66 The Cambridge Shakespeare: the first volume edited by William George Clark and John Glover, and the subsequent eight volumes by Clark and William Aldis Wright |

| 1864 The Globe Shakespeare, a single-volume produced by William George Clark and William Aldis Wright, using their Cambridge texts |

| 1891 W J Craig, The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (one volume) |

| 1986 John Jowett, William Montgomery, Gary Taylor, Stanley Wells, William Shakespeare: The Complete Works (one volume) |

| 2016 John Jowett, Gary Taylor, Terri Bourus, Gabriel Egan, The New Oxford Shakespeare: Modern Critical Edition: The Complete Works (one volume) |

See, Encyclopedia Britannica, Vol. 25, 1911, Steevens George, pp. 868-69; “Old” and “New” Revisionists: Shakespeare’s Eighteenth-Century Editors, Grace Ioppolo, Huntington Library Quarterly, Vol. 52, No. 3 (1989), pp. 347-361); University of London/Senate House Library ‘Shakespeare Metamorphosis’ Eighteenth-century Editions of Shakespeare at Senate House Library, 2018 (online); Hathi Trust Digital Library (online); WorldCat (online); AbeBooks.co.uk; Penny’s Poetry Pages Wiki, Shakespeare’s Editors, Fandom Books Community (online); Internet Archive (online); University of Birmingham Research Portal (online).

THE SHAKESPEARE-BACON THEORY

James Wilmot was a Warwickshire clergyman who lived from 1726 to 1807. A manuscript in the Senate House Library of the University of London, seems to represent two lectures given to the Ipswich Philosophical Society in 1805 by a man called James Corton Cowell. According to this, Wilmot had started trying to write a biography of Shakespeare, but, finding little evidence, decided that the works must have been written by Francis Bacon, which would make Wilmot the first to propose the Baconian theory. But people now have questioned the authenticity of this manuscript. There’s no evidence that either Cowell or the Ipswich Philosophical Society ever existed. In 2010 James Shapiro, in his book Contested Will, showed conclusively that the manuscript is a forgery, done probably in the early twentieth century. In 1786 there appeared the historical allegory ‘The Story of the Learned Pig’ in which the anonymous author makes a mock confession that he himself wrote five plays of ‘the immortal Shakespeare’. ‘Who wrote Shakespeare?’ appeared in Chambers’s ‘Journal,’ 7 Aug. 1852. In 1848 Joseph C. Hart, a New York lawyer and journalist, published ‘The Romance of Yachting’ which included an attack on the idea that all thirty-eight plays assigned to Shakespeare had a single author and that this author was William Shakespeare. According to Hart, it was ‘a fraud upon the world to thrust his surreptitious fame upon us.’ He suggested that in future years, ‘the enquiry will be, who were the able literary men who wrote the dramas imputed to him.’ In 1856 the American Delia Bacon challenged Shakespeare’s authorship in an article in American magazine, (‘Putnam’s Monthly Magazine of Literature, Science, and Art’), called ‘William Shakespeare and His Plays; An Inquiry Concerning Them.’ This was followed by Delia’s book ‘ The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded’ (1857), which developed the theory that the works of Shakespeare were authored by others who used this pseudonym, mainly the writer Lord Chancellor Francis Bacon, Viscount St Albans (1561-1626). Mr. William Henry Smith seems first to have suggested the Baconian hypothesis in ‘Was Lord Bacon the author of Shakespeare’s plays? A letter to Lord Ellesmere,’ 1856, which was republished as ‘Bacon and Shakespeare,’ 1857. Constance Pott started the Francis Bacon Society with its first meeting in 1885, and she published her Baconian theories in ‘Francis Bacon and His Secret Society’ (London, 1891). An American politician named Ignatius Donnelly adopted the Baconian Theory and published ‘The Great Cryptogram’ in 1888, in an attempt to show that secret messages may be detected in a cipher or cryptogram in Shakespeare’s plays. Donnelly came up with the story that Francis Bacon had indeed written the plays, but had concealed his identity with the use of secret ciphers in the text. Francis Bacon did developed his own ‘biliteral’ cipher, but it wasn’t fully published until his first philosophical work ‘De Augmentis Scientiarum’ (1623). However, he did discuss ciphers in general in ‘The Proficience and Advancement of Learning Divine and Humane’ (1605). In the 1887 issue of the North American review, an article by Hugh Black (‘Bacon’s Claim and Shakespeare’s ‘Aye’’, Vol. 145, no. 371, pp. 422-434) made the assertion that he had deciphered the mysterious epitaph that covers Shakespeare’s grave. Black singled out the code FRA BA WRT EAR AY which he claimed read ‘Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare’s Plays,’ and came to the conclusion that the epitaph was written by Bacon, perhaps with Shakespeare’s consent. Dr Owen, an American physician, came up with his own deciphered ‘proof’ of Bacon’s authorship in his book ‘Sir Francis Bacon’s Cipher Story’ (1893-95). Owen’s assistant Elizabeth Wells Gallup, worked on his theories, and came to her own conclusions in 1895. She subsequently published literature that claimed to reveal deciphered messages in the works of Bacon, Shakespeare, and others. In 1899 she published ‘The Biliteral Cypher of Sir Francis Bacon,’ and ‘The Lost Manuscripts’ in 1910. Lord Penzance, a lawyer whose support of the Baconian theory may be found in his ‘judicial summing-up,’published in 1902, expressly admits that ‘the attempts to establish a cipher totally failed; there was not indeed the semblance of a cipher.’ Sir Edwin Durning-Lawrence, in his ‘Bacon is Shakespeare’ (1910), goes still farther in an attempt to prove the Baconian theory by cryptographic evidence. Others such as Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Henry James and Sigmund Freud have expressed disbelief that Shakespeare actually produced the works attributed to him.

Elizebeth Smith Friedman and William Frederick Friedman, both shared the opinion that Gallup’s conclusion that the works of Shakespeare were written by Francis Bacon were questionable. They had worked with Gallup at Riverbank Laboratories which was created by George Fabyan a textile tycoon, who published works by Gallup on the Baconian cipher theory in 1915 and 1916. The Friedmans continued to study the question of the authorship of Shakespeare for the rest of their careers. Through logic and systematic analysis the Friedmans were able to disprove theories claiming that codes appear in Shakespearian text. The Friedman’s rigorous assessment of the works of Shakespeare did not detect a valid code system, which led them to conclude that the text did not contain any codes. Their findings were initially published under the title ‘The Cryptologist Looks at Shakespeare’ which received the Folger Shakespeare Library Award in 1955. The Friedmans’ work was then published as a book in 1957 under the title ‘The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined,’ and the following year they won the fifth annual award of the Shakespeare Festival Theater and Academy. The Cryptology theory was again put forward by IB Melchior in ‘Melchior A La Carte’ (2009).

It is hard to believe that Ben Jonson, who dubbed Shakespeare the ‘sweet swan of Avon,’ who knew both Shakespeare and Bacon very well, and who survived Bacon for eleven years, could have died without revealing the alleged secret, at a time when there was no reason for concealing it. Other alternative candidates for authorship of the Shakespeare canon include Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, Sir Walter Raleigh, and Christopher Marlow.

See, Encyclopedia Bitannica, Vol 24, 1911, Shakespeare William, The Shakespeare-Bacon Theory by Hugh Chisholm; ‘Shakespeare-Who Was He?: The Oxford Challenge to the Bard of Avon,’ Richard F. Whalen, Praeger, 1994, p. 64; ‘Melchior A La Carte’, IB Melchior, Premier Digital Publishing, 2009; ‘The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined,’ The George C. Marshall Foundation; ‘History of Cryptography and Cryptanalysis: Codes, Ciphers, and Their Algorithms,’ John F. Dooley, Springer International Publishing AG, 2018, pp. 25-29; ‘Knowledge is Power: Shakespeare, Bacon, & Modern Cryptography’, Peter Harrington Limited, London, 2019; ‘A Republican Dream? — Americans Question Shakespeare’, Abstract by Kim C. Sturgess, University of Qatar, Borrowers and Lenders, 2005-2020; ‘James Wilmot and Shakespeare’s Authorship,’ Stanley Wells, Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, 2020.

SHAKESPEARE’S GRAVE

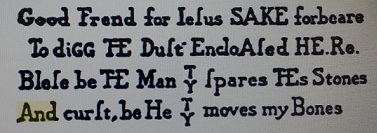

The gravestone on the floor next to the Alter in Holy Trinity Church, has no name, but it presumably covers the remains of Shakespeare. For centuries scholars and laymen have puzzled over the strange epitaph carved into it. According to Halliwell-Phillipps the present gravestone is a replacement for the original, dating from the late 18th or early 19th century. But according to IB Melchior in ‘Melchior A La Carte’ (2009), the gravestone was replaced in 1891, and he offers this as the original epitaph:

Another version of this curious mixture of capitals and smaller letters appears in Hugh Black’s ‘Bacon’s Claim and Shakespeare’s ‘Aye’’ (1887), which he copied from ‘Shakespeare’s Complete Works,’ Charles Knight’s Biographical volume (London: Virtue and Co., c. 1875, p. 542):

The gravestone we see today has the epitaph carved all in capital letters. To the left is his widow Anne Hathway and to the right are those commemorating Thomas Nashe, then Shakespeare’s son-in-law Dr John Hall, then Hall’s wife Susanna. It is often said that Shakespeare had the right to be buried in the church because he was a tithe-holder, and there is some suggestion that he himself composed his cryptic epitaph, and gave explicit instructions for its carving. His gravestone is shorter than the others which could mean it had been broken or cut off and the remnant discarded, or part of it could be hidden under the alter steps. His wife’s gravestone has a memorial brass with Latin verses but is otherwise unmarked. The three neighbouring stones dedicated to members of Shakespeare’s family are carved with both a coat of arms and a memorial inscription. It is odd that Shakespeare’s gravestone reveals nothing to suggest it is his. However, several 17th century visitors to Stratford transcribed the epitaph as belonging to Shakespeare. One of the earliest was John Weever, who transcribed the Latin and English inscriptions from Shakespeare’s monument, along with the epitaph from Shakespeare’s gravestone in about 1617-19 (The Society of Antiquaries of London, MSS 128, fol. 375r). Weever had previously praised Shakespeare and his poetry in ‘Epigrams’ (1599).

It is quite possible that part of the gravestone is hidden under the alter steps, and might be carved with Shakespeare’s name, or bear marks that it once had a memorial brass. Permission was given for the first archaeological investigation of Shakespeare’s grave, which was carried out using a non-invasive radar scan, with a team led by Kevin Colls from Staffordshire University, who also led the archaeological excavation at New Place, the site of Shakespeare’s home. The scan found some surprising details, which revealed that the burial is about three feet deep. Shakespeare and his family were not buried in coffins but simply wrapped in winding sheets, or shrouds, and buried in soil. Most notably the investigation has revealed that there is evidence of a mysterious and significant repair to the head end of Shakespeare’s grave, leading to Kevin Colls theory that this localized repair was needed to correct a sinking of the floor possibly caused by a previous disturbance to the grave. Kevin added: ‘We have Shakespeare’s burial with an odd disturbance at the head end and we have a story that suggests that at some point in history someone’s come in and taken the skull of Shakespeare. It’s very, very convincing to me that his skull isn’t at Holy Trinity at all.’ In addition, Shakespeare’s grave was found to be significantly longer than his short stone – extending west towards the head end, making it the same size as, and in line with, the other family graves. (Anne’s grave is also longer than her stone suggests.) A story published in the Argosy magazine in 1879 claimed that Shakespeare’s skull was stolen from Holy Trinity in 1794. Apparently a doctor named Frank Chambers led a team of grave robbers into the grave. Dr. Chambers supposedly got away with Shakespeare’s skull and later sold it for 300 pounds to the politician Horace Walpole. This tale had been traditionally dismissed as myth, but the archaeological team found it to be surprisingly accurate in its details. In particular, the shallow depth of the grave mentioned in the magazine article matches the measurements produced by the radar scans. The team investigated another story which says that Shakespeare’s skull was in the crypt of St Leonard’s church in the village of Beoley, Worcestershire. The skull was scanned and a forensic anthropological analysis was carried out, as well as a facial reconstruction, which led to the conclusion that it was a woman in her 70s. The archaelogical investigation was the subject of the documentary Secret History: Shakespeare’s Tomb, broadcast on Channel 4 in 2016, presented by the Cambridge historian Dr Helen Castor. The Rev. Patrick Taylor, Holy Trinity Stratford, stated: ‘Holy Trinity Church were pleased to be able to cooperate with this non-intrusive research into Shakespeare’s grave. We now know much more about how Shakespeare was buried and the structure that lies underneath his ledger stone. We are not convinced, however, that there is sufficient evidence to conclude that his skull has been taken. We intend to continue to respect the sanctity of his grave, in accordance with Shakespeare’s wishes, and not allow it to be disturbed. We shall have to live with the mystery of not knowing fully what lies beneath the stone.’

See, The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare, Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 171-72; National Geographic, Meghan Modafferi, ‘Has Shakespeare Lost his Head’ 2016; Staffordshire University Website ‘Staffs Uni academic carries out first-ever archaeological investigation of Shakespeare’s grave’; Secret History: Shakespeare’s Tomb, Channel 4 News Release, March 2016.

SHAKESPEARE’S FUNERARY MONUMENT

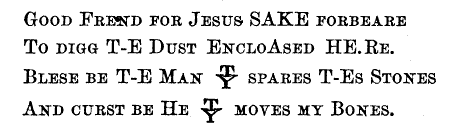

The monument to Shakespeare was installed in the chancel of the Holy Trinity Church sometime between Shakespeare’s death in 1616 and the publication of the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays in 1623. The evidence for this lies in the fact that John Weever, transcribed the Latin and English inscriptions from Shakespeare’s monument, along with the epitaph from Shakespeare’s gravestone in about 1617-19 (The Society of Antiquaries of London, MSS 128, fol. 375r). Also, Leonard Digges, in his elegy to Shakespeare in the First Folio, says: ‘when that stone is rent, And Time dissolves thy Stratford Monument, Here we alive shall view thee soon.’ There is a copy of the monument in the Paster Reading Room at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The sculptured monument has the hallmarks of the ‘Southwark School’ of foreign craftsmen who settled south of the river Thames during the sixteenth century to avoid a ban on immigrant labour which was imposed by the City of London livery companies. They developed a distinctive style which was adapted from work in the Netherlands from where they came, using a colourful combination of materials, particularly alabaster and black marble, enhanced with a great deal of paint and gilding and a bastardised style of classical architecture for the surrounds. The herald and antiquary Sir William Dugdale noted in his diary for 1653 that this monument and that of John Combe nearby were the work of ‘one Gerard Johnson’. His testimony must bear some weight and it points to Gerard Johnson the Younger, a second-generation member of one of the leading Southwark workshops.

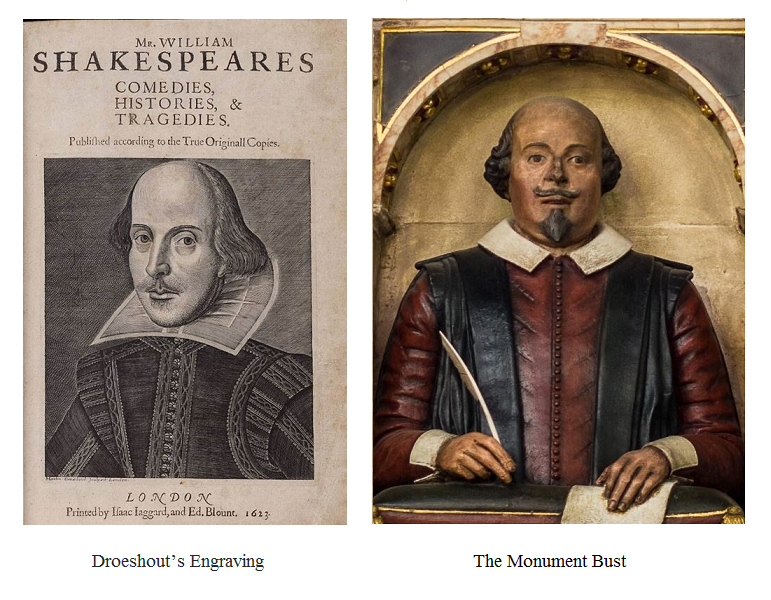

John Aubrey saw the monument sometime between 1640 and 1670 and described what we see today: ‘Mr William Shakespeare [Poet] in his monument in the Church at Stratford upon Avon, his figure is thus, viz a Tawny satten doublet I thinke pinked and over that a black gowne like an Under-graduates at Oxford, scilicet the sleeves of the gowne doe not cover the armes, but hang loose behind. When I learnt to read 1632 of John Brome the parish Clarke of Kington St Michael, his old father who had been Clarke there before) dayly wore such a Gowne, with the sleeves pinned behind. I doe beleeve that about the later end of Queen Elizabeths time ’twas the fashion for grave people, to weare such Gownes’. (Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Top. Gen. c 25, fo 203v).

Shakespeare’s monument is placed on the wall to the left of the row of gravestones, and its inscription mentions only his surname. This, along with certain features of its design, has led to the conjecture that it was intended to surmount a tomb on which more facts would have been inscribed, but that this part of the plan was abandoned. In the floor, close to the monument, is the gravestone commemorating Shakespeare’s wife. Although she died seven years after her husband, her stone, not his, lies directly under the monument. Nicholas Rowe, writing in 1709, said that Shakespeare’s gravestone lay ‘underneath’ the monument, which might mean that at that time it lay directly below it, with the result that no identification was necessary.

The monument bust is believed to have been commissioned by Shakespeare’s son-in-law, Dr John Hall, and is thought to have been modelled from either a life or death mask. There are many so-called ‘casts’ of the busts. George Bullock took a cast in 1814 and Signer A. Michele another about forty years after. The ‘Kesselstadt Death Mask,’ was claimed to be the death-mask of Shakespeare, and it was used to gauge the authenticity of other portraits. It was thought not to be a death-mask at all, but a cast from one and probably not even a direct cast. In three places on the back of it is the inscription +AˆDm1616: and this is the sole actual link with Shakespeare. The mask first came to light in 1849, having been searched for by Dr. Ludwig Becker, the owner of a miniature in oil or parchment representing a corpse crowned with a wreath, lying in bed, while on the background, next to a burning candle, is the date — Ao 1637. This little picture was by tradition asserted to be Shakespeare, although the likeness, the death-date, and the wreath all point unmistakably to the poet-laureate Ben Jonson. Dr Becker had purchased the mask at the death-sale at Mainz of Count Kesselstadt in 1847, in which also ‘a plaster of Paris cast’ (with no suggestion of Shakespeare then attached to it) had appeared. This he found in a broker’s rag-shop, assumed it to be the same, recognized in it a resemblance to the picture (which most persons cannot see) and therefore attached enormous historical value to it. A search for the link of evidence necessary to be established, through the Kesselstadt line to England and Shakespeare, has never been proved or carried beyond the point of conjecture. There are strong arguments against the authenticity of the mask, most notable is the differences between it and the Droeshout print of Shakespeare’s head in the frontispiece of the first folio. The mask was on view in the British Museum, where it was carefully studied by Professor Richard Owen. He was convinced that it was the model used by Gerard Johnson when he created the Shakespeare bust for the funerary monument in Holy Trinity Church at Stratford. Among the many adherents of the theory was William Page, the American painter, who made many measurements of the mask and found that nearly half of them agreed with those of the Stratford bust; the greater number which do not he conveniently attributed to error in the sculptor. The mask was shown in the Stratford Centenary Exhibition in 1864, and is now in Darmstadt, Germany (See, Images Relating to Shakespeare: The D’Avenant Bust (below).

In 1748 the Revd Joseph Greene removed the bust from its moorings to make a plaster cast of the face. As late as 1973, trespassers were able to remove the bust from its niche during the night. Some repair was made to the monument in 1649, and restoration began in 1748 and was completed the following year. John Hall, the limner from Bristol was hired to do the restoration, and he did a painting of the monument in c. 1748, apparently before the restoration. In The Shakespeare Documents, B. Roland Lewis traced the relevant ‘correspondence, notes of meetings, and a bill of announcement’ between 1744 and 1748, including the following excerpt written by the Revd Joseph Greene, then Master of the Stratford Grammar School: ‘the figure of the Bard, [was] taken down from his niche to be more commodiously cleans’d from dust, &c; I can assure you that the Bust & cushion before it . . . is one entire lime-stone.’ (Note that Greene makes an explicit reference to the ‘cushion’.) Greene further assures his correspondent that care was taken, as nearly as could be, not to add to or diminish what the work consisted of, and appear’d to have been when first erected: And really, except changing the substance of the Architraves from alabaster to Marble; nothing has been chang’d, nothing alter’d, except [the] supplying with [the] original material, (sav’d for that purpose,) whatsoever was by accident broken off; reviving the Old Colouring, and renewing the Gilding that was lost. Edmund Malone had the bust covered in white paint in 1793. The colour has since been reapplied, more than once, and this probably accounts for the wooden appearance that can be seen today.

In 1748 the Revd Joseph Greene removed the bust from its moorings to make a plaster cast of the face. As late as 1973, trespassers were able to remove the bust from its niche during the night. Some repair was made to the monument in 1649, and restoration began in 1748 and was completed the following year. John Hall, the limner from Bristol was hired to do the restoration, and he did a painting of the monument in c. 1748, apparently before the restoration. In The Shakespeare Documents, B. Roland Lewis traced the relevant ‘correspondence, notes of meetings, and a bill of announcement’ between 1744 and 1748, including the following excerpt written by the Revd Joseph Greene, then Master of the Stratford Grammar School: ‘the figure of the Bard, [was] taken down from his niche to be more commodiously cleans’d from dust, &c; I can assure you that the Bust & cushion before it . . . is one entire lime-stone.’ (Note that Greene makes an explicit reference to the ‘cushion’.) Greene further assures his correspondent that care was taken, as nearly as could be, not to add to or diminish what the work consisted of, and appear’d to have been when first erected: And really, except changing the substance of the Architraves from alabaster to Marble; nothing has been chang’d, nothing alter’d, except [the] supplying with [the] original material, (sav’d for that purpose,) whatsoever was by accident broken off; reviving the Old Colouring, and renewing the Gilding that was lost. Edmund Malone had the bust covered in white paint in 1793. The colour has since been reapplied, more than once, and this probably accounts for the wooden appearance that can be seen today.

Records show that, over the years, the quill was missing. J. 0.Halliwell-Phillipps described 1748 correspondence that referred to the missing pen. A new quill was ‘refashioned’ in 1790, but an engraving of 1827 shows the effigy, once again, without the pen. In 1908 Sidney Lee wrote that the ‘fingers of the right hand are disposed as if [emphasis added] holding a pen’. The pen may have been missing when the monument was sketched by Dugdale in 1634.

The differences between the various images of the monument has led to some belief that the original had been not only restored, but replaced. In 1844 Peter Cunningham, one of the charter members of what would become the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, declared his faith in the accuracy of Hollar and Dugdale. And in 1904 Charlotte Stopes proposed that the current effigy was modelled upon a 1744 engraving and replaced the original that depicted Shakespeare shortly before his death with his hands laid ‘on a large cushion, suspiciously resembling a woolsack’. Her conjecture was adopted by Sir George Greenwood and became a cornerstone of anti-Stratfordian argument. Both Stopes and Greenwood were rebutted by Andrew Lang in 1912 and M. H. Spielmann in 1923.

An article published in 2006 in the Times Literary Supplement by Sir Brian Vickers asserted that the monument had been installed originally for Shakespeare’s father, John, and later remodelled to suit his poet son. Lois Potter wrote in her 2012 Shakespeare biography that ‘it is not certain whether the [monument] image ever showed the poet.’ A year later, a team of scholars from Aberystwyth University presented a lecture declaring that ‘[t]he original funerary bust remembers a businessman who is clutching a sack of corn, approximately a bushel’s worth, holding it safe and ready to sell to the highest bidder.’ Vickers’ inspiration was a Web page authored by Richard Kennedy, an Oxfordian ‘The Woolpack Man: John Shakspeare’s Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-on-Avon’. Kennedy assumes that Dugdale’s drawing was accurate at the time of execution and argues that the monument originally honored Shakespeare’s father, John. He identifies the large pillow the figure clutches in the drawing as a wool pack, ‘an emblematic token of his mortal accomplishment’.

There is however, no evidence beyond repair or restoration, and it is generally accepted that most of what is seen today is original. William Dugdale’s sketch appears to be inaccurate, which was not unusual for the time, and this has extended to Hollar’s engraving which was copied to some extent by Van der Gucht and Grignion. However, the inscription below the bust appears different in the Hollar and Van der Gucht engravings. The most accurate depiction of the monument must be that by George Vertue, which is derived from his own drawing of the monument and the Chandos portrait. Here the two figures, or Putti above the bust appear to be holding a candle or torch, and next to the Putti is an hourglass and a skull respectively; in the present monument, the hourglass is not visible. In Dugdale’s sketch, Hollar’s engraving, and Van der Gucht’s engraving, the two Putti appear to be holding a spade and an hourglass, and the large cushion held close in the bust appears similar in all three. In Grignion’s engraving there is the similar large cushion, but the Putti on the left is holding an arrow, and the face of the bust appears similar to that in Vertue’s engraving. John Hall’s painting, done before Grignion’s engraving, and probably before the restoration of 1749, is clearly similar to Vertue’s engraving and the present monument.

Many of Dugdale’s original monument sketches are preserved in the ancestral library at Merevale Hall in northern Warwickshire. A comparison with Dugdale’s sketches and the engravings in his Antiquities reveals that the differences between the Shakespeare monument, Dugdale’s drawing, and Hollar’s engraving, such as the incorrect facial features, the disproportionate head and limbs, the cushion/sack, the inaccurate architectural features, and the strangely constructed putti—are found also in other monument representations by Dugdale and Hollar.

Many of Dugdale’s original monument sketches are preserved in the ancestral library at Merevale Hall in northern Warwickshire. A comparison with Dugdale’s sketches and the engravings in his Antiquities reveals that the differences between the Shakespeare monument, Dugdale’s drawing, and Hollar’s engraving, such as the incorrect facial features, the disproportionate head and limbs, the cushion/sack, the inaccurate architectural features, and the strangely constructed putti—are found also in other monument representations by Dugdale and Hollar.

See, Encyclopedia Britannica, Vol. 24, 1911, Shakespeare, William/The Portraits of Shakespeare, Marion H. Spielmann; Reconsidering Shakespeare’s Monument, Diana Price, The Review of English Studies, Vol. 48, 1997, pp. 168-82; The Holloway Pages, Shakespeare Page, Clark J. Holloway, 1999 (online); The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare, Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 171-72; oxfraud.com: William Dugdale’s Monumental Inaccuracies and Shakespeare’s Stratford Monument, Tom Reedy (online); Bath, Art and Architecture, David Bridgwater, 2017 (online); Church Monuments Society (Registered Office: The Society of Antiquaries), Dr Adam White, 2018 (online).

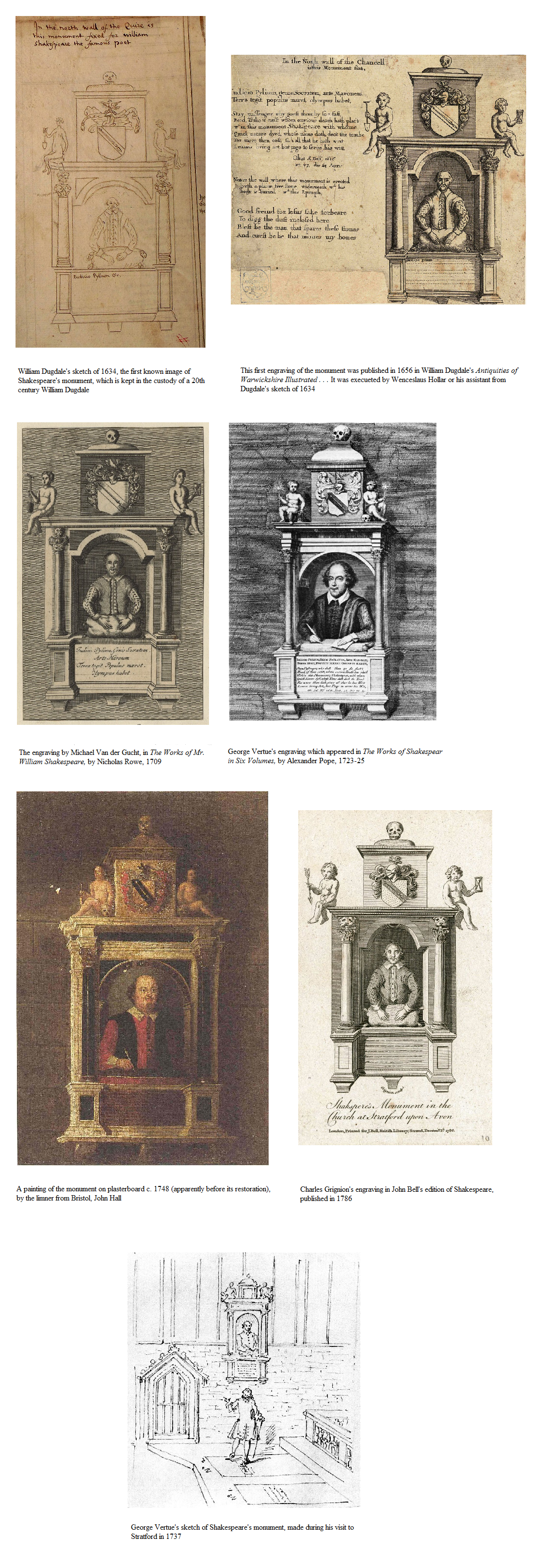

IMAGES RELATING TO SHAKESPEARE

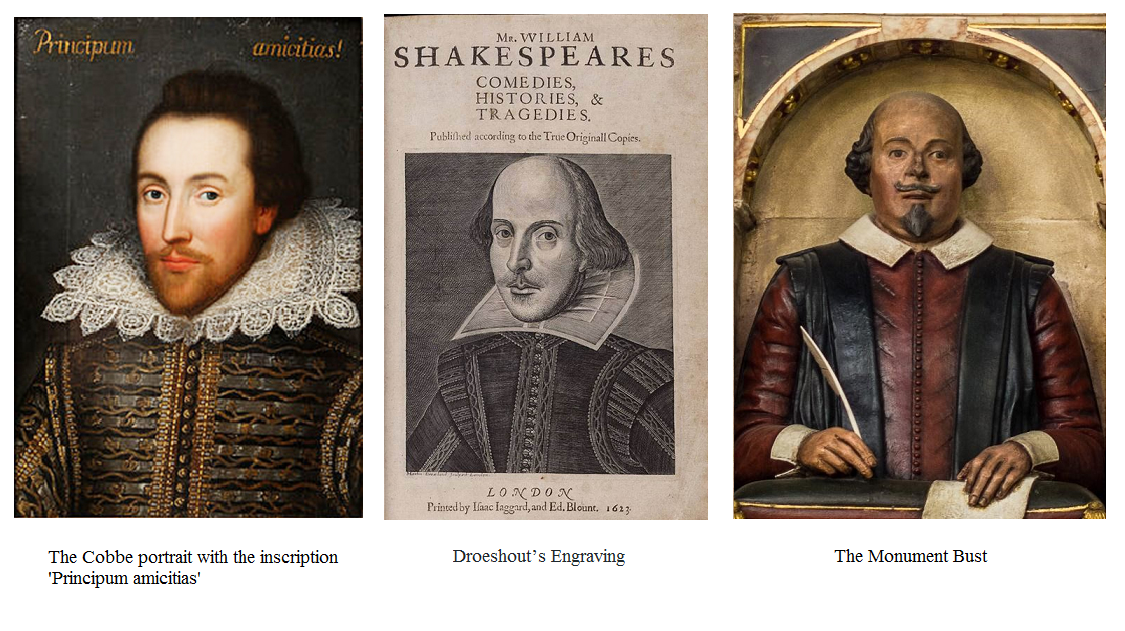

Only two images of Shakespeare can be regarded as authentic, although both appear after his death – the copper or brass plate engraved by Martin Droeshout as frontispiece to the First Folio of Shakespeare’s works published in 1623 (and used for three subsequent issues), and the monument bust in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford upon Avon, which was placed before 1623. There is no definite proof that portraits of Shakespeare were in circulation during his lifetime, but in Return from Parnassus, an anonymous play written in the early 17th century, the character Gullio says ‘O sweet Mr. Shakespeare! I’ll have his picture in my study at the court’.

On the opposite page of the First Folio frontispiece, there are lines by Ben Jonson (who knew Shakespeare well), which suggests he saw the engraving as a good likeness:

This figure that thou here seest put,

it was for gentle Shakespeare cut,

Wherein the graver had a strife

With nature, to out-do the life:

Oh but he could have drawn the wit

As well in brass as he hath hit

The face: the print would then surpass

All that was ever writ in brass:

But since he cannot,

Reader, look Not on his picture, but his book.

There are obvious differences between the two images – the engraving clearly shows a young, slim Shakespeare, whereas the monument bust depicts an older, portly, stiff academic figure. By all accounts the bust is original, although it has apparently been repainted several times. It is thought to have been commissioned by Shakespeare’s son-in-law, Dr John Hall, which would suggest that it was approved by Shakespeare’s widow. It is therefore possible that the engraving is a good likeness of a young Shakespeare, and the bust a fairly accurate depiction of an older Shakespeare.

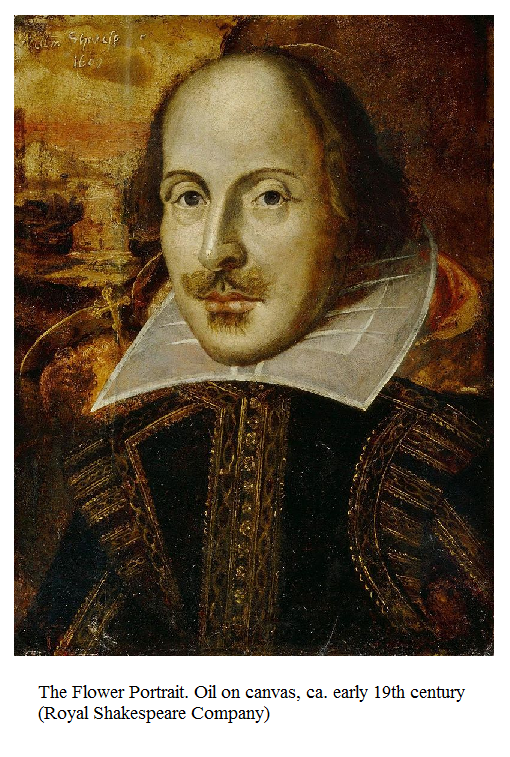

The Flower Portrait

The origins of the Droeshout engraving are uncertain, but an oil painting with ‘Will Shakespeare 1609’ in the upper left-hand corner has a close resemblance to it. Known as the Flower Portrait, it was donated to the Shakespeare Memorial Gallery, Stratford-on-Avon in the late 19th century – a gift from Mrs Charles Flower – it is now in the collection of the Royal Shakespeare Company. It was believed to be a genuine 17th century painting that may have been the original from which the engraving was made. In the early 20th century it was analysed in detail and the conclusion was that it couldn’t have been the source for Droeshout’s engraving, rather the evidence suggested that it was simply a painting of the engraving – the removal of certain features present in the engraving, such as contradictory lighting, shadows and perspective, all point towards an artist seeking to improve on the original.

In 1966 an x-ray, taken by the Courtauld Institute of Art, showed that the Flower Portrait was painted on top of a 16th-century painting that depicts the Madonna and child with John the Baptist – traces of this can be seen to the left of the portrait. This discovery seemed to be proof of an early date – the argument was that a shortage of materials may have caused the Shakespeare artist to cover up the Madonna and child, or that it was covered up due to the anti catholic sentiment in Shakespeare’s time. Experts from the National Portrait Gallery in the UK examined the portrait alongside two others in 2004/5 – they found that some of the pigments, embedded deep within it, and therefore not painted over at a later date, would not have been available before 1814. However there is some belief that the face in the portrait is a mask – due to a dark line running round the left hand side of it – and that behind the mask is a portrait of the real Shakespeare.

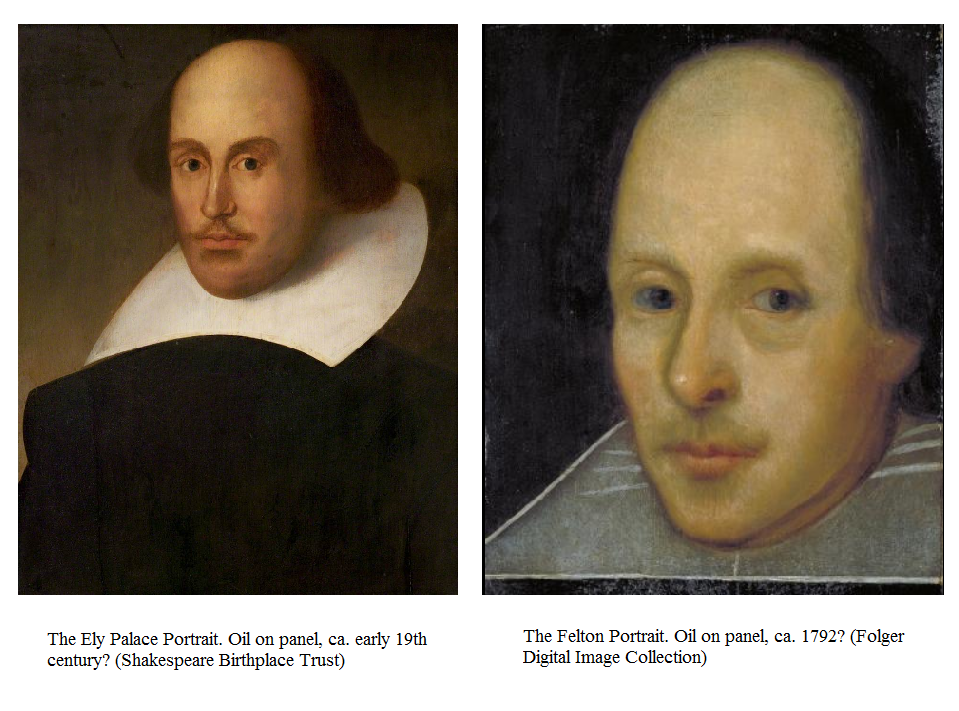

The Ely and Felton Portraits

Two other portraits were believed to have been the source of Droeshout’s engraving – the Ely Palace portrait and the Felton portrait. The Ely Palace portrait was discovered in 1845 in a broker’s shop, and was bought by Thomas Turton, bishop of Ely, who died in 1864, when it was bought by Henry Graves and by him was presented to the Birthplace Trustees at Stratford. It is inscribed ‘æ. 39 x. 1603’ (Harper’s Mag., May 1897). The Felton portrait was purchased by S. Felton of Drayton, Shropshire, in the late 18th century, from J. Wilson, the owner of the Shakespeare Museum in Pall Mall; it has an inscription ‘Gul. Shakespear 1597, R. B.’ (possibly Richard Burbage the actor, who was a business associate and friend of Shakespeare). It was engraved by Josiah Boydell for George Steevens edition of Shakespeare in 1797, and by J. Neagle for Isaac Reed’s edition of 1803. There is no real evidence that either is a life-portrait of Shakespeare.

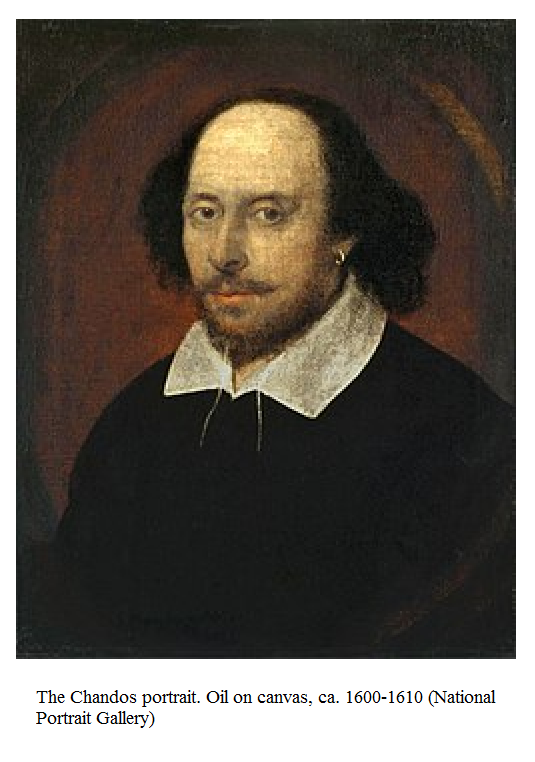

The Chandos Portrait

One of the most famous is the Chandos portrait, named after one of its owners, James Brydges, third duke of Chandos. Earlier owners are said to have been D’Avenant, Betterton, and Mrs. Barry the actress. It subsequently passed, through Chandos’s daughter, to her husband, the Duke of Buckingham. The portrait was purchased at a sale at Stowe in 1848 by Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere, who gave it to the National Portrait Gallery, London – the first portrait acquired by the Gallery when it was founded in 1856. There is some suggestion that it was painted by Janssens or Van Somer, although William Oldys reported that it was painted by Richard Burbage, and had belonged to Joseph Taylor, an actor contemporary with Shakespeare. It is now thought that the portrait was painted by John Taylor, an important member of the Painter-Stainers’ Company. This portrait has a good claim to have been painted from life, and it has been copied many times – it was engraved for Alexander Pope’s edition of Shakespeare (1725). Tarnya Cooper from the National Portrait Gallery has stated that the Chandos has the strongest claim of any of the known contenders to be a true portrait of Shakespeare.

The Cobbe Portrait

In 2009 it was announced that a newly discovered portrait of Shakespeare was made during his lifetime. One of the foremost Shakespearian scholars, Professor Stanley Wells, claimed that an oil painting on wood panel, in the collection of an Irish family, was painted from life around 1610, when Shakespeare was 46. The painting was kept outside Dublin at Newbridge House, the home of the Cobbe family. Alec Cobbe inherited much of the collection in the 1980s, and he placed it in trust at Hatchlands Park in Surrey. In 2006 he saw a painting from the Folger Shakespeare Library, known as the Janssen portrait, which was on exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London. The Janssen had been accepted until the 1940s as a life portrait of Shakespeare, and Alec Cobbe felt certain that it was a copy of the one in his family’s collection. He asked Wells for his help in authenticating it, and the Cobbe painting was subjected to several scientific tests. The results showed that the wood panel on which the Cobbe was painted, dated from around 1610 or earlier, and that it was the source for the Janssen, and there are at least three other copies. Research has suggested that the painting was obtained by the Cobbes through their cousin’s marriage to the great granddaughter of Shakespeare’s only literary patron, Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, who according to some, was the ‘fair youth’ of Shakespeare’s sonnets, and possibly the person who commissioned the Cobbe. A painting of the long-haired earl at 19, also in the Cobbe family collection, was mistaken for many years as a portrait of a young woman.

Tarnya Cooper, curator at the National Portrait Gallery, says she is ‘very sceptical’, and questions Professor Stanley Wells’s main argument: that the Cobbe is the original from which the work known as the Janssen portrait was copied – and that the Janssen portrait represents Shakespeare. Cooper does not deny that the two paintings are versions of the same image; it was common practice to make copies of portraits in the period. But she points out that the Janssen portrait was doctored in the 18th or 19th century to look like Shakespeare. If anything, she says, both works are more likely to represent the courtier Sir Thomas Overbury. ‘I respect Wells’s scholarship enormously,’ she says, ‘but portraiture is a very different area, and this doesn’t add up.’

Wells asserts that Martin Droeshout’s 1623 engraving for the frontispiece of the First Folio was also based on the Cobbe portrait or a copy of it. Cooper disagrees. ‘The costumes are very similar, but that was the fashion,’ she says. ‘Hundreds of men would have worn doublets like that. And the hair and beard – it’s the fashion of the period. One cannot make an argument based on facial resemblance alone. More compelling evidence would include an inscription giving a date, or a coat of arms; a firmer provenance would also be helpful’.

Wells, however, remains convinced. ‘The Janssen portrait was believed to be of Shakespeare until the 1940s,” he said yesterday. “Yes, it had been altered to make it look more like Shakespeare, but we believe that alteration was in fact restoring it to its original appearance.” He added: “In our opinion, the resemblances between the Cobbe portrait and the Droeshout engraving outweigh the differences. We do have a painting that represents what Shakespeare ought to have looked like – a gentleman, who at that time was wealthy, had a coat of arms and land. The case is not 100%, but to my mind is 90%.’

Cooper pointed out that ‘Every five to 10 years, a ‘new’ Shakespeare portrait will appear,’ she says. ‘There are between 50 and 100 images in the National Portrait Gallery stacks that were at one time considered to be him.’

Is the Cobbe portrait a life painting of Shakespeare when he was 46! If so he had an incredibly youthful appearance. Is the Cobbe really similar to the Droeshout engraving and the monument bust in Holy Trinity Church?

The Janssen Portrait

Probably a copy of the Cobbe portrait, the Janssen (oil on panel) has the inscription in the upper left hand corner ‘Æte 46 / 1610’. The first known owner was Charles Jennens, who had acquired it by 1770; a mezzotint by Richard Earlom appeared as a frontispiece for Jennens’s 1770 edition of ‘King Lear.’ By descent the Janssen passed in 1773 to Penn Assheton Curzon, who had married Jennens’s niece. Successive owners were Lord Howe; the ninth duke of Hamilton; the eleventh duke of Somerset; the twelfth duke of Somerset; Lady Guendolen Ramsden of Bulstrode, Gerrard’s Cross; and Sir John Ramsden. There are several ‘copies’: the ‘Buckston’ or ‘Duke of Kingston’ (probably 18th century); the ‘Croker’; the ‘Staunton’; the ‘Duke of Anhalt’; the ‘Earl of Darnley’; and the ‘Marsden.’ The Janssen was originally thought to have been painted by Cornelis Janssens van Ceulen, but he apparently did not come to England before Shakespeare’s death; like the Cobbe, it is possibly a portrait of Sir Thomas Overbury. The Janssen was purchased by the Folger Shakespeare Library, and in 1947 infra-red photography revealed that the bald head depicted in the portrait was due to overpainting, probably done before 1770 – the Janssen was doctored to look like Shakespeare. In 1988 the Folger Shakespeare Library had the overpainting removed, revealing a man with a regular hairline (as in the Cobbe).

There are many faked portraits, such as the Shakespeare Marriage picture discovered in 1872, as well as the Rawson portrait, the Matthias Alexander portrait, and The Belmount Hall portrait. In the early part of the 19th century two clever ‘restorers,’ Holder and Zincke, made a lucrative trade out of fabricating fake portraits of Shakespeare (as well as of Oliver Cromwell and Nell Gwynn). The Stace and the Dunford portraits were named after the unscrupulous dealers who put them forward as genuine images of Shakespeare; a copy of the latter is known as the Dr Clay portrait.

There are many faked portraits, such as the Shakespeare Marriage picture discovered in 1872, as well as the Rawson portrait, the Matthias Alexander portrait, and The Belmount Hall portrait. In the early part of the 19th century two clever ‘restorers,’ Holder and Zincke, made a lucrative trade out of fabricating fake portraits of Shakespeare (as well as of Oliver Cromwell and Nell Gwynn). The Stace and the Dunford portraits were named after the unscrupulous dealers who put them forward as genuine images of Shakespeare; a copy of the latter is known as the Dr Clay portrait.

The ‘fancy-portraits’ are also numerous: The 18th-century small full-length Willett portrait at the Shakespeare Memorial; the many representations of the poet in his study in the act of composition, such as those by Benjamin Wilson, John Boaden, John Faed, R.A., Sir George Harvey, R.S.A., C. Bestland, and B. J. N. Geiger; other portraits, by John Wood, E. Ender, and R. Westall, show Shakespeare reading, either to the Court or to his family; the infancy and childhood of Shakespeare, by George Romney (three pictures), T. Stothard, R.A., and John Wood; and Shakespeare before Sir Thomas Lucy, by Sir G. Harvey, R.S.A., and Thomas Brooks.

There are many engraved portraits on copper, steel, and wood, and also numerous portraits in stained glass that have been inserted in the windows of public institutions. These include the German Chandos windows by Franz Mayer at Stationers’ Hall, and in St Helens, Bishopsgate, and the Droeshout type in the great hall of the City of London school.

Numerous attempts have been made to reconstitute the figure of Shakespeare in sculpture, these include the large seated figure mounted on a great circular base around which are arranged the figures of Hamlet, Lady Macbeth, Prince Henry, and Falstaff, presented by Lord Ronald Sutherland Gower to Stratford and set up outside the Memorial Theatre in 1888. In 1864 J. E. Thomas modelled the colossal group with Shakespeare, showing figures of comedy and tragedy, which was erected in the grounds of the Crystal Palace, and in the same year Charles Bacon produced his colossal Centenary Bust, a reproduction of which forms the frontispiece to John H. Heraud’s Shakspere: His Inner Life (1865).

The leaden statue of William Shakespeare at the Stratford Town Hall was presented to the town by the great 18th century actor David Garrick. It was sculpted by Peter Scheemaker, and John Cheere produced the lead cast with the finished statue unveiled in 1769. Several statues have been erected in other countries, such as the bronze by M. Paul Fournier in Paris, and the seated marble statue by Professor O. Lessing set up in Weimar by the German Shakespeare Society. A statue by J. Q. A. Ward is in Central Park, New York (1872). In 1886 William Ordway Partridge modelled and carved the seated marble figure for Lincoln Park, Chicago; and later, Frederick MacMonnies produced his very original statue for the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

There are Medals and Coins: Jean Dassier (Swiss; in the ‘Series of Famous Men,’ c. 1730); J. J. Barre (French; in the ‘Series numismatica universalis,’ 1818); Westwood (Garrick Jubilee, 1769). The 18th-century tradesmen’s Tokens, which were used as currency, constitute another set of images, about thirty-four of these, including variations, bear the head of Shakespeare.

Portraits in porcelain and pottery, in statuettes, busts, in ‘cameos’ and in painted pieces were produced, and gems with portraits of Shakespeare have been produced since the middle of the 19th century.

By the end of the 19th century portraits and statues of Shakespeare were appearing in numerous contexts, and his stereotyped features were being used in advertisement, cartoons, shops, pub signs and buildings. This led to abstract portraits by modern artists. For the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth, Pablo Picasso in 1964, created several variations of his face. There are also the distorted projections by the Hungarian painter, printmaker, graphic designer and animated film director, István Orosz (b. 1951), and a unique portrait by the folk artist Heather Galler (b. 1970).

There are eight statues circling the Elizabethan Garden by sculptor Greg Wyatt. These represent key moments and characters in each play: The Tempest, Julius Caesar, King Lear, Hamlet, Twelfth Night, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Henry IV, Part 2, and Macbeth. Created by Wyatt for the Great Garden at New Place in Stratford, they were added to the Elizabethan Garden in 2003 and 2004.