William Caxton

William Caxton, the merchant, diplomat, writer and printer, was the first English person to work as a printer and the first to introduce a printing press into England. Born about 1422 in Kent, he began his career at age 14 for Robert Large, one of the most wealthy and important merchants in London, and a leading member of the Mercers Company, an organization of merchants who dealt in textile fabrics. Here Caxton continued until the death of Large, in 1441, and though still an apprentice, left England and appears to have gone to Burgundy, where English cloth merchants had their most active European business connections. He prospered in Burgundy, and by 1463 was made Governor of the English Nation, the Company of Merchant Adventurers resident at Bruges, a diplomatic post, and one at which he was very successful. During this time Caxton interest in the English language increased, he was aware of its shortcomings; essentially it was a patchwork of dialects with no written foundation to maintain stability. He gave up this post to enter the service of the duchess of Burgundy, as a sort of semi-retired advisor and, in the leisure which this position afforded him, he turned his attention to literary work. A visit to Cologne in 1471 marks an important event in Caxton’s life, for there, he saw a printing press at work. If we believe the words of his successor Wynkyn de Worde, he even assisted in the printing of an edition of Bartholomaeus de Proprietatibus Rerum in order to make himself acquainted with the technical details of the art. A year or two after his return to Bruges, he determined to set up a press of his own, and in about 1475 he issued Raoul Lefevre’s The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, the first printed book in the English language. The book was Caxton’s own translation from the French, a project he had begun in 1469, and finished in 1471, due to the encouragement of Margaret, duchess of Burgundy. Two other books were printed in Bruges, The Game and Play of Chess Moralised, and Quatre dernieres choses. In 1476, Caxton returned to England and set up his press in the abbey precincts at Westminster. In the two years following his arrival, he issued a large number of books, though very little from his own pen. We have it on the authority of the printer Robert Copland, who worked for Wynkyn de Worde, Caxton’s assistant and successor, and who might himself have been with Caxton, that the first products of the Westminster press were small pamphlets. This description applies to a number of tracts of small size issued about this time. These are Lydgate’s Temple of Flass, two editions of The Horse, the Sheep and the Goose and The Churl and the Bird; two editions of Burgh’s Cato, Chaucer’s Anelida and Arcite and The Temple of Brass, the Book of Courtesy and the Stans puer ad mensam. Service-books by Caxton include a Sarum Ordinale, and at least four editions of Books of Hours, and the Psalter, Directorium Sacerdotum, and some special services to add to the breviary. He is credited with printing about 100 editions of various books in his shop in Westminster. Twenty one works from Latin, French and Dutch literature were his own translation, and all but one of these were printed by him. Not only was Caxton England’s first printer, type designer, and type founder, he also established England’s first advertising agency. He used his new medium to tell people about his products and services, thus the first English advertising hand-bill was printed, followed by others that periodically advertised the work of his new printing business at the Sign of the Red Pale. Caxton’s greatest contribution was to the English language, he had increased English speaking people’s awareness of the poetry and literature of their time and paved the way for great English writers to follow.

William Caxton, the merchant, diplomat, writer and printer, was the first English person to work as a printer and the first to introduce a printing press into England. Born about 1422 in Kent, he began his career at age 14 for Robert Large, one of the most wealthy and important merchants in London, and a leading member of the Mercers Company, an organization of merchants who dealt in textile fabrics. Here Caxton continued until the death of Large, in 1441, and though still an apprentice, left England and appears to have gone to Burgundy, where English cloth merchants had their most active European business connections. He prospered in Burgundy, and by 1463 was made Governor of the English Nation, the Company of Merchant Adventurers resident at Bruges, a diplomatic post, and one at which he was very successful. During this time Caxton interest in the English language increased, he was aware of its shortcomings; essentially it was a patchwork of dialects with no written foundation to maintain stability. He gave up this post to enter the service of the duchess of Burgundy, as a sort of semi-retired advisor and, in the leisure which this position afforded him, he turned his attention to literary work. A visit to Cologne in 1471 marks an important event in Caxton’s life, for there, he saw a printing press at work. If we believe the words of his successor Wynkyn de Worde, he even assisted in the printing of an edition of Bartholomaeus de Proprietatibus Rerum in order to make himself acquainted with the technical details of the art. A year or two after his return to Bruges, he determined to set up a press of his own, and in about 1475 he issued Raoul Lefevre’s The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, the first printed book in the English language. The book was Caxton’s own translation from the French, a project he had begun in 1469, and finished in 1471, due to the encouragement of Margaret, duchess of Burgundy. Two other books were printed in Bruges, The Game and Play of Chess Moralised, and Quatre dernieres choses. In 1476, Caxton returned to England and set up his press in the abbey precincts at Westminster. In the two years following his arrival, he issued a large number of books, though very little from his own pen. We have it on the authority of the printer Robert Copland, who worked for Wynkyn de Worde, Caxton’s assistant and successor, and who might himself have been with Caxton, that the first products of the Westminster press were small pamphlets. This description applies to a number of tracts of small size issued about this time. These are Lydgate’s Temple of Flass, two editions of The Horse, the Sheep and the Goose and The Churl and the Bird; two editions of Burgh’s Cato, Chaucer’s Anelida and Arcite and The Temple of Brass, the Book of Courtesy and the Stans puer ad mensam. Service-books by Caxton include a Sarum Ordinale, and at least four editions of Books of Hours, and the Psalter, Directorium Sacerdotum, and some special services to add to the breviary. He is credited with printing about 100 editions of various books in his shop in Westminster. Twenty one works from Latin, French and Dutch literature were his own translation, and all but one of these were printed by him. Not only was Caxton England’s first printer, type designer, and type founder, he also established England’s first advertising agency. He used his new medium to tell people about his products and services, thus the first English advertising hand-bill was printed, followed by others that periodically advertised the work of his new printing business at the Sign of the Red Pale. Caxton’s greatest contribution was to the English language, he had increased English speaking people’s awareness of the poetry and literature of their time and paved the way for great English writers to follow.

A Selection of Printed Works

c. 1476 Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

1477 Dictes and Sayings of the Philosophers (the first dated book issued in England, translation by earl Rivers).

c. 1477 The History of Jason, translated by Caxton from the French version of Raoul le Fevre.

1478 The Moral Proverbs of Christine de Pisan (translation by earl Rivers).

1479 Cordyale, or the Four last things (translation by earl Rivers).

1480 and 1482 Two editions of The Chronicles of England. This was the history known as The Chronicle of Brute, edited and augmented by Caxton himself.

c. 1480 Ovids Metamorphoses, translated by Caxton, and presumably printed.

1481 The Mirror of the World, Reynard the Fox and The History of Godfrey of Bologne, three of Caxton’s own translations.

1482 The Polychronicon of Higden, which was Caxton’s revising of Trevisa’s English verion of 1387, and writing a continuation, bringing down the history to the year 1460. This continuation being the only piece of any size which we possess of Caxton’s original work.

c. 1483 The Pilgrimage of the Soul and Lydgate’s Life of our Lady, were issued, and also a new edition of The Canterbury Tales.

c. 1483 Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, and House of Fame.

c. 1483 The Golden Legend, Caxton’s most important translation.

1483 Gower’s Confessio Amantis.

1484 Caton, The Book of the Knight of the Tower, Aesop’s Fables, The Royal Book, and The Order of Chivalry, all five translated by Caxton.

1485 The Life of Charles the Great, The History of Paris and Vienne, and Sir Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur.

1487 The Book of Good Manners, Caxton’s translation.

1489 The Fayttes of Arms, Caxton’s translation.

c. 1489 The History of the Four Sons of Aymon and The History of Blanchardyn and Eglantine.

1490 The Eneydos, translated by Caxton.

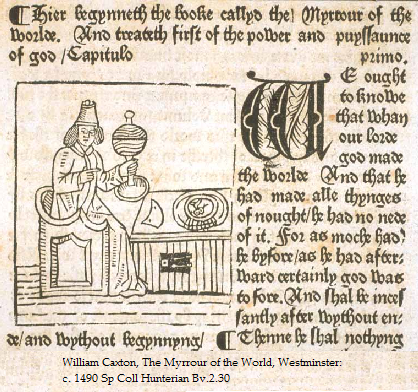

c. 1490 The Mirror of the World, second edition.

1491 Caxton died, having just completed a translation of St. Jerome’s Lives of the Fathers, which was printed by his successor in 1495.

This page contains information found in Typographic Milestones, Allan Haley, 1992; The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21), Volume II. The End of the Middle Ages, XIII. The Introduction of Printing into England and the Early Work of the Press; The Cambridge History of Early Modern English literature, David Loewenstein and Janel Mueller, Cambridge University Press, 2002.